- Home

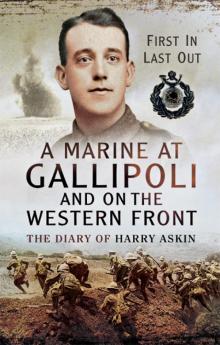

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 3

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 3

Chapter Two

25 April 1915 – Action

Arrived somewhere off Gallipoli about 2.00am from our own calculations. We were about the NW part of the Gulf of Saros, lying somewhere off the Bulair Lines, the narrow neck of the peninsula, said to be heavily fortified.

About 5.00am Canopus and Dartmouth started a bombardment of the Turkish positions. This carried on for an hour, we being very interested spectators. This was the first touch of real warfare that most of us had experienced. We could see the bursts of most shells but, of course, not the effect. Nothing came at us in return and the two destroyers went close inshore and shelled the Turk. We got news about 3.00pm that 29th Division and our Plymouth Battalion had landed at Cape Helles, and the Australian Division at Gaba Tepe, and were getting on fine.

About 5.30pm we all moved about three miles nearer shore and some ships commenced lowering boats. We were only supposed to be making a landing here to keep so many thousand Turks from reinforcing their other positions. Heard that one officer, Captain Freyberg,1 had volunteered to swim ashore after dusk, tow a small raft with him and then let off so many lights that were on the raft. He did it, though we didn’t see the result as we received orders to steam south and stand by to land. As far as I could make out only the three marine battalions moved; the others carried on with the dummy landings,

I was fast asleep below when we stopped at Gaba Tepe and never heard the bombardment. Some chaps heard it, and the rattle of rifle and machine-gun fire too, so we must have been fairly close inshore. We were on the move again when I got on deck and I noticed that nearly all our boats had gone from the davits. They had been lent to help get the wounded off, and to land troops, as most of the other boats had been sunk when the Australians landed.

We were steaming very slowly and by noon came up to the armada lying off Cape Helles. There were about sixty more transports and scores of warships, both French and British, and every available gun on them was blazing away for all they were worth; from the 4-inch guns of the destroyers to the great 15-inch guns of the Queen Elizabeth. She was simply overwhelming in action and when she fired four of her 15-inch guns and then a broadside of 6-inch the concussion was terrific. We kept drifting about all that day and the next, sometimes finding ourselves close alongside a cruiser or a battleship just as she was firing, sometimes drifting close enough inshore to see the efforts of the landing parties, struggling to get guns and stores on shore, all the time under heavy shrapnel fire from the Turkish batteries.

We could see bunches of sixes and eights bursting every few seconds. It must be terrible there for our chaps, but what about poor Johnny Turk, with all our ships pumping HE2 into them?

At times we should receive curt orders to clear out of it, but we kept drifting back every time. We could see the castle of Sedd-el-Bahr in a battered condition and behind it the village of the same name, almost flattened to the ground. Visible about twelve miles north-west was the big hill at Gaba Tepe, where the Australians were fighting. Towards dusk it presented a terrible appearance, the whole place one mass of flames, smoke and bursting shells. We had nothing to do but stand on deck and watch. I wondered what the people at home would think to it all, and how much some people with heaps of money would pay to see it all, with the same safety and comparative comfort with which we saw it? And if we had heaps of money, how much would we give to get out of it? Our turn ashore was sure to come, so it was no use kicking and, really, I think there were very few aboard the ship who were not anxious to have a turn. I slept on deck and slept sound. Up again on the 28th with the first streaks of dawn and found things just as busy. Both sides were blazing away and some of our ships appeared to be getting it hot. Great spurts of water kept shooting up into the air around them. They were the misses. We couldn’t see the hits.

We steamed up to Gaba Tepe at noon and watched the fun there, a repetition of Cape Helles. Were we only spectators in this game, or were we to take an active part in it? We were! Two destroyers came up alongside about 3.00pm and we received orders to get things ready for leaving. We had a jolly good meal about 4.30, the best we had had on the Gloucester Castle and then bade the ship’s company a ‘soldier’s farewell’.

B and D Companies were taken off on the Harpy, A and C on the other destroyer. We heard lots of news from the sailors about the landings. The 29th Division was going strong and about five miles inland now. Our Plymouth Battalion had landed at Y beach with the KOSB3 and had had no casualties. Their advanced guards had entered Krithia, but had not met with serious opposition; the whole lot were then rushed right off the peninsula again.

The Australians had lost heavily and were still losing heavily which, of course, was awfully bucking to us, as we were to join them. I had no forebodings, however, and felt nothing but a mild excitement and satisfaction at having something definite to do. I noticed that old Tom Watts, our company quartermaster sergeant major, and Joe Broster, our sergeant major, looked worried and anxious. They had seen service in China, South Africa and, recently, at Antwerp, and evidently expected something more than fun and a novel experience. I was still holding the position as observer to Major Clark, so had to stick to him and carry his periscope. The destroyers took us as far inshore as they dared, then we were transferred to tows (strings of boats towed by a steam pinnace) which took us to the beach. We had a quiet landing, not a shell being fired at us. The reason for that was obvious: every available ship was blazing away like mad, to keep down the fire of the Turkish batteries. Luckily for us they achieved their object. We got ashore but what a state of absolute chaos everything was in – stores, ammunition, guns and discarded equipment all mixed up together. Naval officers, from admirals downwards to stokers who had volunteered for work on the beach, mixed up with the Australian generals and staff officers. There was a dressing station just under the cliffs and the tarpaulin shelter was ripped in scores of places by shrapnel. There were strings of Australians and sailors who had been wounded waiting to be dressed, while just a few yards away under the shelter of the cliff were scores of poor chaps who had passed beyond dressing. I seemed to realise then that it wasn’t going to be all fun. I think I can rightly claim to have been the first one ashore out of our battalion, that is in the rank and file. I followed Major Clark onshore and had heaps of running about to do.

Old Clark immediately got dizzy and had me flying around in all directions. First to platoon commanders – ‘Have your platoon got on shore yet and if not, why not?’ – then to find the colonel, who was about half a mile away talking to General Birdwood of the Australians, and report D Company ashore. Then I had to chase after the company which had done a move and was about a mile along the beach. The Australians were jolly glad to see us and some told us what an awful time they had had, and were still having. The number of killed and wounded was awful and, as we moved along, fresh wounded were being carried down to the dressing station. Others were walking and all of them, if they were at all conscious, were swearing horribly and cursing the Turks.

We rested in a small open space by the sea until it was dark and were then guided by Australians up a deep gully for about half a mile. It was pouring with rain but we hardly noticed it, our minds being too much occupied with other things. First of all were the wounded, who were being carried past us faster than ever now that it was dark; then there was an incessant clatter of rifle and machine-gun fire from practically all round us, and it sounded jolly near too. We rested for about half an hour in the gully and while seated with Major Clark a runner came up to us. He was an Australian, caked with mud and almost speechless through running. He was gasping out for the officer commanding Portsmouth Marines, so I switched him on to Major Clark and he gave him this message: ‘From Colonel Monash4 of the Twelfth Australians, would Portsmouth Battalion follow the runner, as his troops were being heavily attacked by the Turks and can’t hold them back much longer.’ Of course, Major Clark couldn’t do anything, but told the chap to wait until Colonel Luard came back. No one saw the ru

nner after that; he just faded away into the night. One guide suggested that he was very likely a German who, had we followed him, would have led us into the Turkish lines.

We picked up two more guides after that and commenced a climb up the steep slope of the gully. The earth was slippery with the rain and it was a case of going up two and coming back one. I had the job of hauling up old Clark, then that fool Domville with his huge Barr and Stroud range-finder. Several times I felt like kicking him and his B & S to the bottom again. All around us lay signs of the fight, broken rifles, equipment and caps. We had on those great sun helmets and I took a sudden dislike to mine, so slung it away and picked up a cap, apparently lying on the ground, but when I came to touch it I found a head inside it belonging to a dead Australian. He had been shot through the head and there were the two holes in the cap where the bullet had passed through.

Our guides disappeared after a short time and we were left to wander about on our own. We had no idea where we were, or where we had to go, until somebody challenged us. It was an Australian officer who had just been attending to several wounded men who lay groaning in a hole nearby. This chap said he had been waiting for a relief for what had been his company, so he took us on. Just above us was a shallow communication trench and we passed up this for about fifty yards, then came to the firing line which was full of Australians. To avoid a crush we walked along the top and the other fellows began to file out. They had ceased fire as we came up, but not so the Turk. The sound of firing that we heard with comparative safety an hour ago was unpleasantly close now, and bullets were whizzing by us. I was walking ahead with Major Clark and the Aussie officer and when we came to the left of our company sector old Clark told me to get in. I was pleased to do so. I don’t know if those Turkish bullets were close but they sounded so. The Australian I dropped in by told me to dig and keep on digging; said it was hell down there ‘and don’t be afraid of that chap in front of the parapet. He’s dead and we’ve just thrown him out’. Then he went down the trench. I could see more than one dead one as I looked over the top. As they had got killed their chums had just rolled them over the top, firstly to form a parapet for cover and, secondly, to get them out of the way. One could hardly call this a trench; it was more like a series of holes, none more than three feet deep and with connections between them about a foot deep. On my left was a dead end but about six feet beyond I could see where the trench began again, but no signs of anyone in it. Found out that instead of being with my own platoon, No. 15, I was with No. 13, Dornville’s platoon. I had no idea who was on my left. I had only my entrenching tool to dig with but managed to get down a bit. The fellow next to me would insist on throwing most of his dirt down my neck. It was all chalky stuff and terrible to dig. What a night! Quietness on our part, then, after a time, quietness on Johnnie’s part, a suspicious quietness, and the rain came pouring down. I was looking out whilst resting from digging and after a time felt certain that I could see someone moving out in front, so I did the expected – fired a round. Word flew up the line at once, from Domville I suppose: ‘Who the devil fired that shot and why?’ I sent word back, ‘Private Askin fired’, and ‘what are we here for.’ I thought our war had started. I claim that to be the first shot fired in our battalion. The excitement died down a little and I carried on digging again, but it was both back-aching and heartbreaking work. My hands were soon blistered and I was just about ready to throw the dammed tool over the top when an order came up the line ‘Turks advancing, rapid fire’, and we ‘rapid fired’ and blazed off enough ammunition on that occasion to blow all the Turks out of Europe. Then another order ‘Turks retiring, cease fire.’ Several times up to dawn we got those orders repeated and it was a continual change between digging and rapid fire.

It’s a wonder we were able to fire at all, what with the muddy state of the ammunition and the red-hot rifles. Blaze away we did though, aim or no aim, Turks or no Turks. Sometimes we could see black masses moving towards us and could hear the yells of the Turks; other times we could see nothing but the black night.

With the first streaks of dawn came our first experience of being shelled. They started slinging shrapnel shells just over our lines, bursting nicely for them but awfully terrifying for us. Everybody had the wind up. I found the benefit of my digging then. I had dug low under the dead and had undercut it, so when I crouched low down in that, felt fairly safe.

The smell from the explosive was horrid and nearly choked us. We took it in turns to keep watch while the shelling was on, about one man in every six being up. As the first spasm of shelling died down we observed some men digging away to our right front, so sent word down to Major Clark to see if we could fire at them. He sent word back that they were our own men. I had my doubts. The sergeant in charge of No. 4 Platoon A Company had a good look at them through his glasses and said he thought they were Turks digging a machine-gun pit. We left them alone but had plenty of sport across to our front. The Turk had adorned his trench with green branches and small bushes but we spotted a few heads moving occasionally and tried hard to hit them. He could see ours too, I should imagine. We must have looked like a lot of Aunt Sallies sticking over the top of the trench. Every now and again a bullet would whizz just above our heads, then one would plonk into the parapet, knocking a shovel of earth over us. It was only the shells that made us take cover though, and as soon as we heard one coming down we got. About 7.00am I was feeling awfully dirty, and as my water bottle was full felt justified in using a little for a shave. Just as I started with the razor, the Turk started with his infernal shrapnel, but after the first violent duck I was able to carry on. Felt heaps better after a wash round with the brush and more like a feed than I had done before, so shared a tin of bully beef and jam with Smith, the chap next to me. A few hard biscuits and a drink of water furnished the repast. It wasn’t very elaborate, but I felt like a new man after it and ready for anything. Got word up shortly afterwards that young Willoughby had been killed, sniped through the head while trying to get a Turk. Soon after we heard that Corporal Matthews had managed the same thing. Had several casualties a bit later with shrapnel. I didn’t like those shells a little bit, although the first terrifying effect had gone off. The nose caps were the worst to me. They seemed to come whizzing down on their own long after the shell burst.

Our ships opened up about 10.00am and quietened the Turkish batteries a bit. I could see our huge shells bursting right up this great mountain and it made me think how little right we had to grumble. We are only getting about 12- or 16-pounders while they are getting anything up to 12-inch shells weighing about 240lb or more, lots of them filled with Lyddite; those shook us up considerably. Smith got up to have a shot. He spotted something, took a very careful aim and was just going to loose off, when something hit his rifle, smashing it in two and a splinter of the wood went into his arm. He thought he was hit and so did we. We got the splinter out and he carried on with an Aussie rifle; there were plenty knocking about. Dead Australians, and Turks too, were lying about in profusion and we could smell them when the sun got up. It got scorching hot towards midday and our water got low.

Major Clark sent word up for me to take his periscope down to him, but I didn’t intend leaving my cosy spot, so sent him his silly old thing. I had found no use for it and could see heaps more by putting my head over the top.

I got in some decent sniping, with what result I wouldn’t swear, but I’m not a bad shot and the targets at times were very fair and the range no more than 200 yards. Johnny got in some good sniping too. He made me duck a few times and filled my eyes and ears with dirt. We kept getting word up the line about different chaps getting killed and wounded. Colour Sergeant Blanchard of A Company, a Bisley man and one of the best shots in the marines, got sniped through the head; it would appear that the Turk had some fair shots too. Another rotten doing with shrapnel after dinner; more bully, jam and biscuits, not water. One fellow offered to take about ten bottles to the bottom of the gully and get them fille

d. He came back after about two hours and said he’d had to dig a hole and wait for the water to ooze in. It was more mud than water but it tasted good to us. I wonder where those thousands of tins of water were that we brought from Port Said? I hadn’t seen one yet since landing. Some of our fellows had a scrounge round at the back of the trench and searched some dead Australians and Turks. They got plenty of souvenirs and luxuries in the way of food from the Aussies, but nothing from the Turks and the water in their bottles was warm and stale. Carried on improving my trench but I found that if I dug much more I should not be able to see or fire over the top.

Night came on again, cold and with a heavy dew that soaked through and through me but, thank heaven, no shelling. The Turks must have been afraid of hitting their own trenches. We could see a huge red glow in the sky all night and word was passed up that our ships had fired the fort and town of Great Maidos. We had a repetition of the previous night, attacks real and imaginary by the Turks, with wild bursts of firing by us. When the Turks came they came in thousands and we must have hit some, otherwise they would have reached us. I managed about an hour’s sleep, the first since landing. I was awakened out of it by someone falling on to me. It turned out to be our doctor going along the trenches to attend to any wounded who couldn’t be moved. He asked if we were alright and passed on his way. With the dawn came the shrapnel and more casualties. We had none. It must have been a lucky corner because we got plenty of shells. Threw my equipment on the back of the trench while I did a bit of digging and when I came to put it on again found that half my pouches had been blown away and most of my ammunition exploded. Something heavy must have hit them and it was a good job I hadn’t them on at the time. Some big shells went over about noon and we could see them drop in the sea near one of our battleships. We surmised that they were 11-inch shells from the Goeben. What a terrible rushing sound they made as they went through the air.

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front