- Home

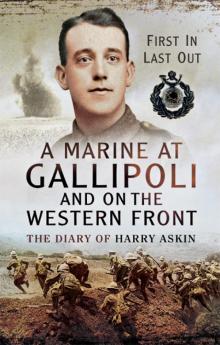

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 2

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 2

Heard news on Sunday of our attempt to force the narrows and what it had cost us in ships and men. The Ocean, Irresistible and the French ship Bouvet had been sunk while nearly all the other ships that had taken part were more or less damaged. Scores of ships came in the next day and it gave us the impression that we had given up all idea of getting through the narrows.

Some of our sergeants rowed over to the Queen Elizabeth for a chat with some old shipmates and procured tobacco, books and papers, and glowing accounts of what the ship and her 15-inch guns had done to the Turks – smashed up all the forts and shelled the Goeben as she lay off Chanak. The Lizzie had been hit three times but none of the shells had done serious damage.

The 23rd saw more signs of moving and we left Lemnos at 4.30pm. Heard from some of the ship’s crew that we were bound for Egypt. I hoped we had seen the last of Mudros. The place had got on my nerves. Had a lovely voyage and came in sight of the harbour works and lights of Alexandria about 5.00pm on the 25th.

Up early next morning, anxious to get a good view of the town. It looked a lovely place, some change from the dirty-looking places on Mudros. Lots of troopships there and not far away were eight German cargo boats. We were soon surrounded by native boats, most trying to sell us things but, as usual, we were not allowed to trade with them and, as usual, we had no money. Several well-off looking Arabs in flowing robes of brilliant colours tried hard to get on board. They pleaded urgent business with the captain or any old thing, but they couldn’t bluff the quartermaster at the gangway. How they all scattered when the native police boat came on the scene. A few individuals were allowed on board just before lunch, amongst them a greasy-looking Arab lad selling Egyptian mails at 3d a time [1p]. Very few of us were well enough off to sport 3d. Ready to sail again about 5.00pm. Just about then an American cruiser came into harbour; absolutely one of the latest, telescope masts and other fancy arrangements, but not half so business-like looking as our ships.

Said goodbye to Alex about 5.30pm and steamed due east, making for Port Said. Heaps of fishing boats were outside Alex and appeared to be having a pretty rough time with the weather. Arrived at Port Said at 7.30 next morning and had a very slow job getting berthed. The whole place was packed with shipping and most of our divisional ships came in about the same time as us. Some were already landing stores and troops and we were told to get everything ready for landing. Passed the day gazing at the drab and uninteresting surroundings. Arab kids came round us in boats, pestering us to throw pennies in the water. It was amusing at first to watch them diving for the money, bringing it up every time in their mouths, but it got tiring and we started slinging things at them. Granted shore leave from 5.00 to 8.00pm. Took advantage of it and had a walk round with two chums. Struck the native quarter first and what a smell. Worse even than Mudros. We were not allowed to enter the native quarter. Several soldiers had been killed there, so guards had been placed on the approaches. I hadn’t the slightest desire for a closer inspection of the place.

Made our way to the English part of the town which was much better and cleaner, but which still had that horrible smell. Senior and I borrowed some money from Robinson and bought a few postcards and a bit of chocolate. Anything in the way of souvenirs was quite out of the question. There were plenty of good shops, cafes and hotels, all doing a roaring trade. Somebody must have had a payday. We got back to the ship alright, but some of the chaps had to be carried on board. Landed next day at 2.30pm and a proper good time we had. Although we had horses and mules on board we never used them but dragged everything ourselves. Limbers and GS3 wagons full of stores tents, marquees, kitbags and ammunition had to be pulled from the ship to where we were to pitch our camp, half a mile from the ship with every inch over loose sand a foot deep. Several journeys like that, then to pitch camp for our own company. It was done at last, but what a day’s work. The hardest I ever remember. There was a small canal about 200 yards away and we had a bathe in it. What a relief!

All the naval division were encamped together and it made an enormous camp, thousands of tents pitched in order. We were put fourteen in a tent. It was hot but we all slept well, the first night on shore for a month. Had a change for breakfast – bacon, native cooked bread, jam and a drop of good tea. The lines of our camp didn’t suit Colonel Luard and about 9.00am the whole battalion was at it stripping and re-pitching camp, all working to whistle signals. Micky Sanders was busy and dizzy as usual and Major Clark was like a mad bull. Leave in town again after tea but it was pretty miserable having no money. Parade next morning at 8.15am in full marching order for an inspection by General Trotman. Practised various stages of the attack after that, and in a sandstorm. We sank ankle deep in the sand every step we took and, with the wind getting up, clouds of sand buried us. We were full of sand and fed up to the teeth. Packed up at 12.30, had dinner, then a bathe in the canal. The water was dirty and the bottom slimy but it was lovely and cool inside. All the tired feeling disappeared and when we got to camp we were paid 10/- [50p] each, so were able to indulge a little after tea. Made ourselves ill eating Turkish delight and Jaffa oranges. Dirty-looking natives tried to take us down, wanting about 20 piastres for little trinkets worth about 2d [1p] and most probably made in Birmingham. There were heaps of lovely things in the shops, but the prices were too extortionate for a poor marine.

The next morning Micky Sanders picked on me to act as observer to Major Clark. Clever job. I had to stick to old Clark during the attack like a limpet and know exactly where everybody else was, read the thoughts and intentions of the colonel, and take note of all signals. It was a tricky little job, but far better than being a common ordinary soldier, having to make mad rushes at imaginary foes, flopping down in the sand and getting mouths, eyes and nose full of the stuff. I used to like the attack best when our company was on its own. We started off in artillery formation about 2,000 yards from the objective, deployed about 1,000 yards and then advanced by rushes, first by platoons, then sections, then a few men at a time. Everybody used to get dizzy and, as we came by each stage, dizzier still. About 100 yards from the objective, Major Clark and I would walk on and take up a position where we could see everything. He would then give the signal for the final stage of the attack. The lads would fix bayonets and, strange as it seems, would put lots of energy into that final charge, yelling like madmen the whole time. We had Divine Service on Good Friday in full marching order and after that carried on the attack, with the mercury in the glass at a hundred and something in the shade. We had night operations at 4 o’clock next morning, then at 9.00am fell in for an inspection by General Sir Ian Hamilton. About the hardest and most tiring time we’ve had for some time. Finished up with a march past, companies in line.

Granted leave from 2.00pm on Sunday, so had a good luck round. Went along the seafront and on one of the main breakwaters saw the statue to Ferdinand de Lesseps, the man who designed the Suez Canal. Went to a picture show after that, but it wasn’t very interesting; all the titles were in French. Had tea at a French café and did ourselves well. Then back to camp early. Orders next day to stand by to embark at 2.00pm. Got all gear ready, gave in one blanket per man to go with kitbags to the base at Alex, and cleared up the lines. The order to move was cancelled, of course. Re-embarked at 10.00am on Wednesday 7 April, and found out we had mules and horses on board. The next day we took on board thousands of four-gallon tins of fresh water. The base party with Major Abrahall left us for Alex. We left Port Said at 9.30pm and anchored outside for the night. In the morning we took in tow a lighter full of the tins of water. We must be going somewhere hot and dry.

Set off at 10.00am on the 9th; the pace was just killing and at times we hardly appeared to be moving. We had to stop several times and some of the crew would have to chase after the lighter which kept breaking adrift. Sighted the Islands again on Sunday morning and shortly after received orders about submarine defence. We mounted machine guns round the ship and rigged telephones to them from the bridge but sighted noth

ing and came up to Mudros about 7.00pm on the Monday, too late to get into harbour as the boom closed at sunset.

Jack Senior and I made up our beds on the well deck as usual but had to turn in below as the weather was dirty. Awakened about 2.30am by the violent rocking of the ship and the noise of mess utensils as they flew from one side of the mess deck to the other. We could hear the water dashing over onto the decks and the crew dashing about. Then there were some frightful bumps and after that the noise and excitement died down and we dropped off to sleep again.

Heard in the morning that the ship had run her bows between two big rocks on the coast and the lighter kept bumping into the side, then she got in the way of the propellers which cut her in two. So ended the fresh water, and the only lighter out of dozens that actually reached Mudros. We were battened down below but the officers were all on deck with one of them on his knees, crying and praying. He oughtn’t to have left his Mam. Got into harbour at 7.30 next morning and found it even more packed with shipping than before. Several more huge battleships were in, or so it appeared, but on close inspection we found them to be dummies, old tramps converted into modern first-class battleships and cruisers. General Trotman transferred to our ship from the Braemar Castle in the afternoon with all his staff. Our ship’s company profited by that move. When we left the ship at Port Said a steward was supposed to come round to each mess table and take over all mess utensils, then make a list of any shortages. Some messes were complete and others were just short of a few oddments, perhaps a knife or spoon or a brush of some kind. What a surprise though when the bill was presented. It amounted to two or three shillings for each man. We kicked but only quietly and in consequence our officers took the matter through for us. Several of our senior officers had meetings with the ship’s captain and purser and told them in the end that they must apply for the money through the Admiralty. It was settled at that until the general came on board and the question was then brought up again with the result that we had to pay. I think this ship carries about the rottenest lot of swindlers I’ve ever struck. They half starved us, then, at night, would sell us what was left over from the officers’ dinner.

We were in the bay until Friday, during which time we got rid of our tins of water. A battleship took all ours. We left Mudros again at 7.30am on the Friday and, just outside, received a wireless message from the troopship Minotaur to the effect that she had been attacked. We put on steam and moved faster than we’d ever done before, steering a zigzag course to avoid being hit ourselves. Two companies were told off with their rifles, and machine guns posted round the ship again while everyone was told to keep a sharp lookout for periscopes. Sighted about half-a-dozen ships later on lying close together with the cruisers amongst them. Several ships’ boats were passing from the ship we made out to be Minotaur to the Royal George. We could do nothing, and were told to clear off. We had no idea of what had happened but, while in Alex later, I had the story from a sergeant of the RFA in 29th Division who was on board at the time.

The Minotaur was on the way from Alex to Mudros with the 29th’s field artillery. The guns were on deck but all ammunition was below and they had no means of defence. I expect they were like us and had forgotten all about the war. It was early in the morning when a torpedo boat came up alongside. Everyone thought it was British until she hoisted the Austrian flag and the captain spoke to the Minotaur and asked if she was carrying troops, but didn’t wait for an answer: he just gave the order to fire. Three torpedoes were fired but, with the ships being so close together, they passed harmlessly under Minotaur. The Austrian boat then made off, making no attempt to shell the other. A panic started immediately on the Minotaur which the captain helped considerably by shouting ‘Every man for himself’. There was a rush for the boats and two, lowered full of men, dropped in the water wrong side up. Between fifty and sixty soldiers were drowned as a result. That stopped the panic and no one else was eager to leave the ship. Our cruisers went in chase and eventually drove the Austrian onto a nearby island and shelled her into a complete wreck.

We carried on our way and presently came near to a large, rocky and mountainous island. The nearer we got to it, clearer and more blue the water appeared to get. It was a glorious day and a pleasure to be on the sea, and the knowledge that a little danger was near only added to our pleasure. We were all keeping a strict lookout for enemy craft and, as we approached the island, some of us got a shock. A boat of some kind left the coast and tore towards us at a terrific pace. I really thought we were in for it and, as it came nearer, could make out a gun in her bows. However, our hopes and fears were dashed as it turned out to be nothing more than a steam pinnace from HMS Canopus with a pilot on board to guide us into harbour. The island was Skyros, the most interesting and picturesque of the whole bunch that I had seen. It had a fine natural harbour, one side of the entrance being a steep cliff several hundred feet high and the other a great mountain rising steeply from the water’s edge. All along the edge were huge rocks of pure marble. We anchored in umpteen fathoms of beautifully clear blue water and could follow the chain as it went down a long way. The old battleship Canopus was in, also a troopship. Canopus did look a pot mess; her crew were painting dazzle patterns on her. The light cruiser Dartmouth came in but didn’t stay long and later we could see her patrolling the mouth of the harbour. Several more of our ships came in during the day, including the Royal George, which had brought in the dead from the Minotaur. A party went over to the Franconia next day and brought back our kitbags and the base party. The Royal George left during the morning with flag at half-mast but came back later with it flying full mast. The inference is obvious. We landed the next day but didn’t stay long on shore. It was just to practise landing and then have a stand easy. The only signs of life ashore consisted of birds, lizards and snakes, with millions of insects of various kinds. Some of the lizards were lovely looking, one we saw being about twelve to fourteen inches long and a brilliant green. We chased several until they shed their tails through fright. Most of the vegetation consisted of herbs and the smell from them was lovely. What a contrast from Portiana and Port Said. Two French transports and a Red Cross ship came in. Things were looking more like business every day.

Several huge battleships and cruisers were patrolling about outside and one of them, according to some long-service men, had to be the Princess Royal, but as she was in the North Sea, this one must have been a dummy. So, I think, were the others. I wonder what the Turk thinks to all our ships? Landed again on the 19th in FMO4 with cooking utensils and blankets. All officers’ luggage was taken ashore too, and we expected to stay the night. Started off without anybody getting definite instructions about where to land.

All the boats formed a tow and we rowed about an hour and a half before we struck the proper place. Then we had to lump all our gear about 500 yards over rocks and rough ground to the place where we were to pitch our bivouacs. The first job was clearing the place of stones. There were millions of them. It must rain stones out here on the islands. Then we had a dizzy time putting the bivouacs up. They were our own blankets and we had spent hours on the ship making eyelets in them for this job. The officers had three bell tents between four. We had the bivouacs between six.

The usual stew for dinner. Always stew on land. We had a stand easy after that and could bathe and ramble about near the camp. I didn’t fancy bathing, although the water was so cool and tempting. I saw two native fishermen in a boat and the fish they were catching were small octopus. Dozens of them they had stuck on long canes. The brigadier came along later on and inspected our camp and, shortly after tea, we received orders to pack up and get back to the ship.

Landed again next morning, every available man and full marching order. All the division were having a field day under the command of General Sir Archibald Paris. And what a field day. We were supposed to be making an attack on some objective six miles inland. Our battalion was supporting, and our route lay over a huge mountain, one huge mass of rocks a

nd shifting stones.

The ships were supposed to bombard for half an hour, then we would advance half an hour and the ships would have another go, and so on. Our share apparently consisted of alternately crawling and stopping up this huge hill. It was a terribly hot day and, with about 80 or 90lb hanging onto us, we very soon got fed up and done up too.

Back again on the ship about 6.30pm. We had a severe thunderstorm at night but I slept through it, and on deck too. I found it much better on deck than down below in a hammock. All the ships were ready for sea on the 21st but nothing happened until Saturday the 24th. I could feel somehow that things were coming to a head, but wasn’t it time they did? Six weeks on this rotten ship with a war on.

All the divisional ships left Skyros at 6.30pm with Canopus, Doris, Dartmouth and two destroyers as escort. Submarine and mine guards were mounted and everybody was worked up into a fever of excitement. Surely, something was going to happen now after all this time and preparation? We had lectures during the day on our conduct and general bearing towards the Turkish civilians during our victorious march to Constantinople, it being an assured fact that we should get there. We were to be sure to take off our boots before entering a mosque and on no account to lift a woman’s yashmak. This and much more we were told.

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front