- Home

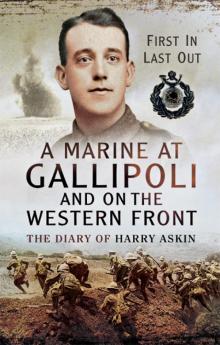

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 26

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 26

We got news along that Company Sergeant Major Milne of C had been killed by a shell during the night. He was digging some of his men out of a fallen house when he got it. Damn it all, there is good in the worst of ’em. There was none of the rejoicing at his death that might have been expected from the old Portsmouth crowd. With them, the men who knew him on the Gloucester Castle and Gallipoli, he was the most hated NCO who had ever been made. I remember the time on Gallipoli, at Backhouse Post, the rejoicing throughout the whole battalion when word flew round that Sergeant Milne was wounded, and the genuine regret when we knew that it was only a very, very slight wound in the neck from a very tired bullet that had travelled at least four miles. Poor old Milne, gone at last, and gone like a soldier.

The Bosch concentrated most of his artillery on the village during the day and the amount of stuff he dropped into it was simply tremendous, nearly all 8-inch shells, and what was once a solid, square-towered church was very soon a heap of powdered stone.

We had to shift our position during the day to a trench no more than knee deep that lay close behind the church and we had a terrible time. We soon got it deep enough to give us head cover and we needed it too. Lumps of 8-inch shell casing kept whizzing down amongst us and several of our company were badly hit. A 5.9 right in the trench where No. 2 Platoon was accounted for seven men, four blown to bits and three terribly wounded.

What with the heavy shelling, poor cover, no sleep and plenty of hard work, nerves began to fray a little at the edges and some of the men began to be a bit jumpy. It’s always a bad sign when men crowd together in a trench and we had all our work cut out to keep them in their places. Several kept on about having no water, Kelly Clayton being one of the most persistent, so I sent half a dozen off under Willet, now lance corporal, to the village where there was a decent well. Jerry had been fairly quiet for half an hour but they had no sooner got to the well than he opened up again with a score of guns right on the village. Lance Corporal Willet, Clayton and another chap came back, the others had been killed outright at the well. Needless to say, no water came back and we had to sit on Kelly to stop him from bolting.

Our aeroplanes had been getting it hot all day and we saw four driven down in flames in less than two hours. They were our artillery spotting planes with open fuselage and petrol tanks in a conspicuous position above the pilot and observer. They were patrolling over the Bosch lines about 800 feet up, not caring a damn about the anti-aircraft shells which were bursting in scores about them, or about the countless rifle and machine-gun bullets that were fired at them from the Bosch lines. All at once a German fighter would drop out of the blue, get behind our man’s tail and let fly with about half a dozen tracer bullets into his petrol tank. Poor devils, they hadn’t a chance, the plane was a mass of flames in less than a minute and in three instances we saw the pilot and observer jump from the plane about 500 feet up. Their fate was obvious. In the fourth case the two men stuck to their machine and managed to get it to within a hundred feet of the ground when it crashed just behind our support lines. The Bosch straightaway sent over a salvo of shrapnel and got a few of our men who had dashed over to help the two airmen. These little incidents got our blood to boiling point and we would cheerfully have dashed over the top for a smack at the Bosch. As we couldn’t do that we took to cursing him and our own fighting planes, not one to be seen anywhere. Then we cursed the men who were responsible for sending out such old-fashioned and out-of-date planes. They should have been scrapped ages ago, or in any case they should have had a few of our fighting planes to protect them.

Just as dusk drew on we observed a German aeroplane flying very low over our front line and the ruins of the village. Of course, we all opened up on him with our rifles but he took no heed and presently he dropped two red lights and a green one. It was obviously a signal for his artillery and we had to crouch down for a full hour. The amount of shells those hellhounds sent over was simply overwhelming and for long into the night we were all more or less dazed.

If we had to take any ground off Jerry with his present strength and attitude we would need far more men than there appeared to be round there, and a lot of luck too. There appeared to be nothing wrong with the German morale; if we could hold on to what we had we would be jolly lucky.

The night was a repetition of the previous night, alarms and excursions on both sides, a terrible ghastly night of sudden spasms when every man stood to and the imagination of one windy individual would set the guns of two corps firing like mad. Dawn came and with it another intense barrage by both sides, but after another hour things quietened down to normal. I think both sides were pretty well exhausted.

About 10.00am on the 27th, after a meeting of our officers with the CO, Wanky Mitchell sent along for platoon sergeants to go to him to get plans of the attack. Jim Hearne went but after about half an hour he was back and the expressions he used about our worthy officer are really not fit to print.

He took the sergeants out over the open into the village and got them all seated in a newly-made 8-inch shell hole. There, instead of telling them about the attack, he started preaching to them, ‘Were they prepared to meet their God?’ It’s much he didn’t meet his there and then, but Mr Hardy kept them quiet and, after about ten minutes, sent them back to their platoons. They left Mitchell in the shell hole, protesting for all he was worth that he wasn’t mad, but Mr Hardy said he was going straight over to the CO to report him.

We knew the attack was to come off about dawn but that was all we did know. Colonel Hutchinson came along and had a talk to Mitchell and took him back to Battalion Headquarters to see Jimmy Ross. They decided to keep him there, which was a big relief to us all.

No doubt we should want every man we could get hold of to carry us through, every tooth and nail, but we certainly didn’t want a blithering lunatic in charge. We pottered about during the day, improving the trench, but what for God only knows; very few of us would ever see it or want it again after that night.

Jerry kept at it all day, pounding the ruins of Gavrelle into the dust, and the only place that had any walls standing at all was the mayor’s house, standing right in the front line.

Our aeroplanes were very conspicuous by their absence and Jerry certainly ruled the roost in that respect. Only twice did our spotting planes try to get over and, in both cases, they were chased to the ground. One was fortunate and dropped to earth behind our own lines; the other was unlucky and came down behind Jerry’s supports. We watched the two airmen scramble out of the plane and nip off for the nearest trench; they had no sooner left the plane than it burst into flames, probably fired by the pilot.

About four o’clock in the afternoon Jim Hearne said he was going to see Mr Hardy. He wanted more details about the stunt, but he never reached Hardy. He was back in about five minutes, his face livid and his right hand shattered by either a rifle bullet or a piece of shell casing. He was in terrible agony and Billy took him back to Jimmy Ross after we had put his first dressing on it. No more fighting for Jim and I was in charge, absolutely in charge, of No. 1 Platoon A Company 2 RM.

When Billy Hurrell got back I went along to inform Hardy of what had happened and on the way back practically the same thing happened to me. A lump of red-hot casing from an 8-inch shell struck me on the back of the left hand and I turned nearly sick with the pain and shock. My hand was badly cut about, but I felt certain that nothing serious had happened to it. I got back to Billy and told him what had happened, then on to Jimmy Ross. I had to wait about half an hour before I could get near him; he was going at it as hard as he could go with casualties. If things carried on in this fashion, no one would be left to attack at dawn.

Jim Hearne was still there and awaiting a favourable opportunity to go back down the line to 1st Field Ambulance. He was in a terrible state of exhaustion and could hardly summon enough interest in things to ask what was wrong with me. When the time came for my turn I felt a lot better and after Jimmy Ross had bandaged it up I felt re

ady for the line again. I told him so and he said I had better go down to Field Ambulance with the next batch. ‘No thanks, Doctor,’ I said, ‘give me a drink of hot tea and I’ll go back to the company.’ He let me go at that, but I couldn’t help thinking what a damn fool I was. Chance to get away to hospital and wouldn’t take it. Maybe I would have lost the chance by morning.

I wasn’t feeling very happy about things and hadn’t that confident assurance of getting back out of it all. For one thing I’d missed my usual ‘Good luck mate’ and for another thing I didn’t like the way the Germans were taking things, not a bit like a beaten army. To me they seemed as ready to attack as we were and their artillery was every bit as powerful as ours. Then again they certainly had the upper hand in the air.

I expect it was the failure of the French offensive in Champagne and the withdrawal of several divisions of German troops from the Russian Front. Anyhow, whatever it was, Jerry had his tail up.

About half past six we received orders to move forward to a section of trench just behind the firing line. From there we should move forward about midnight to the tape which the Royal Engineers would lay out at dusk. We got in the trench but I never thought anybody would get out of it alive. Billy, three men and I got in a fire-bay, the traverses of which were filled in with very recent shells. After about ten minutes Jerry started lobbing 8-inch shells over. He must have had three guns working on a stretch of trench no more than fifty yards long and he did everything but hit us. We were all simply terrified for half an hour, dashing about from one spot in our little bit of trench to another in a frantic effort to dodge the shells. I don’t think I’ve ever been in such a state of funk before and the five of us were too helpless to curse after about ten minutes of it. By then Jerry had missed us with so many shells that we felt certain that one of the next was almost bound to hit us.

No one, who has not been through a similar experience, can have the faintest conception of what we felt like. And all the time I couldn’t help but think that if only I had taken Jimmy Ross’s advice I should have been well out of it all. All good things come to an end and Jerry piped down a bit and shortly after our heavies retaliated with 6-inch and 9.2s all in the German wire and front line. We were watching them burst and giving forth curses of satisfaction when our people happened to drop one in his trench. One 9.2 dropped short, right in our own front line, and we soon had word up that it had accounted for twenty of our men, mostly killed. We had word along about 11.00pm to stand by to move over to the tape and we moved at midnight.

Just as I put my hands on the parapet of the trench to pull myself up some stumbling nervous fool stepped back with his hobnailed boot right on my gammy hand. My curses brought up Mr Hardy who was checking us over and when he saw the blood dripping from the bandage, insisted on me going back to Jimmy Ross. I said I’d carry on, I could still hold my rifle but he wouldn’t hear of it. ‘My God, Sergeant,’ he said, ‘if I’d half your chance I’d take it and be thankful.’ Bob Bayliss was standing by and whispered fiercely ‘Get back out of it, you bloody fool.’ I’d very little heart left with which to tackle the fight and I was nearly all in with the pain from my hand and with the fatigue and nervous strain of the past few days, but still I didn’t like packing up. However, like a good soldier, I obeyed the last order and got back, and the boys went over to the tape, where they had to lie shivering with cold and fear until zero hour at 4.30am.

After much searching I found the doctor’s dugout, the entrance of which had been filled in two or three times during the evening with the shelling and the surrounding trench battered out of all recognition. He was having a bit of a stand easy, having just got a batch of wounded away to 1st Field Ambulance. He looked to my hand, cleaned it and put on a fresh bandage and then told me I had better wait until the next batch was ready to go down. We had a chat together about Gallipoli days and then he advised me to get a bit of sleep. I found a corner but, although I was nearly dead with fatigue, I couldn’t sleep a wink. My thoughts were with the boys and zero hour.

I was dozing when, at 4.25am, with barely a streak of light in the sky the battle began. With a soul-splitting crash, our barrage opened up and the Bosch straightaway put down a counter barrage and the whole front was a mass of flame, smoke and lumps of flying metal.

The very earth shook and we all expected our dugout to fall in on us, but we daren’t go outside. Shells were falling in scores and, by the sound of things, mostly 5.9s and 8-inch. It would be as well here to give a few details of the attack and the objectives to be carried out. The front stretched from Monchy on the right to Arleux on the left. On the left were the Canadians, then 2nd Division at Oppy, then the RN Division, and on the right XVII Corps.

The objective of 2 RM was the ridge of high ground just on the left of the village, the tit-bit of the whole position being the windmill, nothing like a windmill now but a strong fortified position held in full strength by the Bosch.

First Royal Marines were to attack on the left of our battalion; and their main element was enfiladed from a strongpoint on the single line of railway just beyond the windmill. The windmill was attacked by Lieutenant Newling and a party of men who captured it, killed every Jerry in it, and held it against three or four vigorous counter-attacks. Owing to the attacks on both flanks failing, the main body of our battalion had to fall back and by noon the attack had failed. Only the windmill held out and if ever a man deserved the VC it was Newling.

The Bosch was running reinforcements right up the Douai-Arras road in motor-buses and sending them against the windmill, but Newling and his little band of thirty men never budged an inch. He stood up on top of the trench and flung Mills bombs at them as fast as the men could pass them to him. For that he got the Military Cross and two Honourable Artillery Company officers, Lieutenant Pollard and another, got the Victoria Cross for taking a strongpoint on the railway. Petty Officer Scott and fifteen men of the Ansons on the right were isolated during the night of the 28th/29th and had to fight their way back in the morning, bringing in with them 250 German prisoners. Had he been an Australian it would have meant the Victoria Cross. There is no doubt that when a Naval Division man got the Victoria Cross he more than earned it.

Hardy’s presentiment proved to be only too correct. The poor devil was shot dead somewhere round the windmill and, as far as we knew, his body was never found; the money he had on him too is still going begging.

Sergeant Major Chapman was killed, Bob Bayliss was taken prisoner, or so Billy thought, and that brilliant soldier Hobson walked straight over the top as soon as it was light with his hands above his head. I hope the swine got killed!

Joe Woods, the first man in Sedd-el-Bahr castle was killed. Billy told me that he fought like a tiger. Good old Joe, the finest soldier that ever went over the top and the biggest damned nuisance down the line that ever worried an NCO.

Jimmy Ross sent me down to the Field Ambulance about 9.30 am on the 28th with the first batch of walking wounded, but I may as well finish with the attack before I carry on with my own troubles.

During the whole of the 28th and well into the morning of the 29th the Bosch counter-attacked time after time against the village and all the sick-bay men and even the doctor had to turn to with rifles and fight the Bosch in the village. He got as far back as Battalion HQ and things looked very serious for a long time. It was not until about midnight on the 29th that he was pushed back away from the village and his last line of defence.

Very, very little had been gained, except that our hold on Gavrelle had been strengthened by the taking of the windmill position. And the losses were out of all proportion to the little that had been gained.

Our battalion alone lost in killed ten officers and 200 men and the total in killed, wounded and missing was over 600. The 1st Royals lost their Colonel Cartwright and six other officers killed and over 500 other casualties. The casualties for the division in the fighting from 15 April up to the morning of the 30th, when they turned over to the ill-fated 3

1st Division were: killed forty officers, and 1,000 men. The total killed, wounded and missing was 170 officers and 3,624 NCOs and men.

On being relieved, the division returned to the comforts and luxury of the battered dugouts and trenches of the Rochincourt area.

Chapter Twenty-Nine

28 April 1917 – The Pleasures of being Wounded

I made my way down to Rochincourt with a party of walking wounded and reported at the 1st Field Ambulance. After a bit of waiting we were all told to bare our chests and, after a painting with iodine, were inoculated for tetanus. The syringe they used for the job was like a young garden syringe, and the sergeant pumped pints or nearly pints of the stuff into me. It made me feel as sick as a pig and I almost reeled over from the effects of it. Then came examination of wounds, then cleaning and dressing and, as soon as we were finished with, bundled into waiting ambulances and rushed off to the 20th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). I did nothing there but have a feed and scrounge around and begin to feel sorry that I had come away from the line.

About teatime we made our way down to the railway siding and settled down in the hospital train for Étaples where a lot of us were sent to the 26th General Hospital. There the usual procedure had to be gone through: strip, have a bath and roll into bed. I didn’t waste much time before getting off to sleep.

First thing next morning I was down at the stores hut for a new uniform, but I was so early that I upset the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) sergeant in charge and he went off alarming at me. He must have taken me for a full private, but I soon disillusioned him. I told him I wanted a nice-fitting tunic and three neat chevrons to stitch on the right arm so that people would know I was a sergeant and then three gold stripes1 for the left arm. He even fished out needle and cotton for me at the finish so that I could sew them on.

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front