- Home

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 25

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 25

Our 189 and 190 Brigades were to attack the village of Gavrelle and advance their line to about 200 yards beyond. The sight of our guns firing was simply stupendous, one I should imagine will never fade from the memory. The strafe put up for us at Beaumont-Hamel was something, but this far outweighed it. As far as the eye could see, all along the horizon, was one mass of flame and the crash of guns was simply stupefying. Ahead of us, lying just under the ridge of skyline, were the field guns, almost gun wheel to gun wheel. Behind those the 60-pounders, then the howitzers 5-, 6-, 8-, 9-, and 15-inch, bringing up the rear. Amongst the lot was a sprinkling of naval guns mounted on railway trucks. All were blazing away as fast as ever they could go; the sight of it all pictured Hell better than any artist could do it.

The bombardment was by no means one-sided and German shells were bursting amongst our guns with terrible effect. Ammunition dumps were going up in a sheet of red flame in all directions and God knows how many guns were being smashed out of action with their crews blown to bits. It was almost impossible to miss them, they were so close together.

As the light got better we could see events more clearly on the ridge in front. Ammunition limbers going forward at the gallop to feed the guns and lots of them made contact with Jerry’s shells, which were dropping in tremendous numbers all over the place. Our vantage point was none too safe but we stuck it. It was a sight worth seeing and was a good parallel to the fleet shelling Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. Scores of planes were in the air, fighting to the death, and several of both sides came crashing to earth, most of them in flames. Civilisation! The sight of this would make a crowd of cannibals sick with disgust.

So much for the part of the picture we could see, what of the infantry creeping and crawling about amongst the crashing ruins of Gavrelle with the fear of death in their hearts.

About 9.00am batches of wounded and prisoners made their appearance and from the wounded we got snatches of news. The attack had been fixed for 4.45am, a most cheerful hour. The first line of attack for our division was, from right to left, Drake, Nelson, 7th Royal Fusiliers and 4th Bedfords with the Hoods under Asquith as close support for 189 and 1st Honourable Artillery Company (1 HAC) as support for 190 Brigade.

There were three objectives: first, the line of trenches in front of Gavrelle; second, a road running north and south through the centre of the village; and third, a line roughly 300 to 600 yards the other side of the village. Drake, Nelson and 4th Bedfords had taken their first objective in ten minutes and with few casualties. The Royal Fusiliers on the left, however, had been held up on the uncut wire and were practically wiped out. The fighting for the second objective had been far more fierce and losses were heavier, but the road through the village had been gained on schedule. The commanding position, however, the windmill on the ridge of the high ground to the left of the village, was still in German possession, and showed no signs of falling. The Germans were in full strength and fighting mad, and pouring in reinforcements by the thousand.

In the rush for the third objective (which by the way was never gained) all our battalions suffered terrible casualties. A mixed lot under Commander Asquith succeeded in reaching the far edge of the village and commenced digging in front of the cemetery, and Asquith took possession of the mayor’s house and captured the garrison, most of whom he found asleep in the cellars. On this precarious line they awaited the inevitable counter-attacks. And they came, the first about 1.00pm, and took some stopping too; but that was nothing to the second which came off about 4.00pm on the 24th (the next day). Jerry had been massing all night and morning and his artillery was in mighty strength. So was ours, and after some terrible fighting our two brigades managed to consolidate their guns.

Early on the 24th I was warned off as platoon guide to go with a small party of officers of the battalion to reconnoitre some former enemy trenches on top of the ridge, the trenches we were to occupy during the night prior to going forward to the front. Our way lay across country for a bit, through the heavy guns, all firing away like mad, then into a deep railway cutting which led to the top of the ridge. Walking up that cutting put the fear of death into us. There was no cover of any description and Jerry kept lobbing 8-inch shells right into it every few minutes. Lengths of rail were torn and twisted into the most grotesque shapes and heavy sleepers were smashed into splinters. Dead and maimed men were lying about in various attitudes, one or two with still a twitch or two in their limbs.

We arrived at 189 Brigade Headquarters after a time and a gruesome sight met our eyes. About ten men were lying dead in a group, just where the galley was. The cooks were serving out breakfast just before we arrived and an 8-inch shell had dropped amongst them. Ten killed outright and about twenty badly injured. You talk about a queer sensation at the pit of the stomach. We were all pretty well hardened, all sentiment and feeling for others killed in us by our previous scraps, but yet, after the few weeks away from close shelling, away from the horrible sickening things left by the war, we all felt that sinking feeling, that twitching of nerves and muscles that takes possession of one for a time.

I suppose it’s fright, pure fear of death or mutilation, and you feel that you want to run screaming away from it all. I don’t think it is cowardice for a chap to feel that way so long as he does keep control of himself. It’s a feeling that soon wears itself out. Familiarity breeds contempt. We picked up a guide at Brigade Headquarters and he led us up out of the cutting, for which small mercy we were thankful, and into the trenches on the right of the cutting.

There were two lines of them, sadly knocked about and with none of the deep, safe and comfy dugouts usually associated with Bosch trenches. We walked round our battalion sector and took note of the parts allocated to our respective companies and platoons, and managed to have a look at the surroundings. Field guns were stuck all over the place, hardly any being in prepared gunpits, but sticking out in all their nakedness. Shells were dropping amongst them even as we looked and half a dozen 5.9s dropped right in a battery, knocking out two of the guns.

What happened to the guns crews I couldn’t say with certainty, but when we first looked the guns were firing. When the smoke had cleared away, there wasn’t a man to be seen. We saw parts of the guns blown into the air and perhaps some of the spokes were wheel spokes and perhaps they were limbs of Royal Field Artillery (RFA) men. It’s hard to tell from a hundred yards away.

We stayed in these trenches about an hour then made our way back to the railway cutting. We got to the edge when a terrible rushing sound over our heads made us all pause. Just above us was one of our triplanes rushing to earth. We could see the pilot, even the expression on his face, so near was he. He looped the loop twice in a frantic effort to regain control, then his machine nose-dived and crashed in front of a battery of 18-pounders about forty yards away. The pilot’s fate was obvious, poor devil! A crowd of artillery men rushed to the spot but nothing could be done; the plane had burst into a sheet of fierce flame and the remnants of the pilot would never be found.

Several fresh bodies were lying about along the railway track, but things were a little quieter as we made our way back to the battalion and joined them without further incident. I stopped for a few minutes about fifty yards from one of our 15-inch howitzers. Its crew of about fifty men had just got it ready for firing and, as they fired, I could see the huge shell as it left the muzzle and soared its way into the heavens until it was no more than a tiny speck. ‘There’s a hell of a bump coming for some Bosch,’ I thought as I joined up with the others.

Chapter Twenty-Eight

24 April 1917 – Gavrelle and a Few Casualties

The battalion moved up about 3.00pm and took over the trenches on the ridge. We had quite a number of 5.9s amongst us during the day but very little damage was caused by them. The field guns round about us appeared to be the object of the shelling and they must have suffered enormous losses. Battery ammunition dumps were going up in flames all over the place. We had only to stop in these t

renches for a few hours until dusk, before moving forward to relieve our other two brigades who were badly in need of rest.

A little stunt was also on the plans, but we could get nothing from our captain, Wanky Mitchell. If ever any man was mad and unfit to be in charge of a company of men, Wanky Mitchell was the man. Lieutenant Hardy, one of our other officers, told us himself that he was mad and he’d thought of mentioning it to the CO. Hardy himself wasn’t very happy about things. He used to be as cheery and happy a soul as any in the battalion, but since coming up the line he had been horribly depressed and hadn’t mended things much by consuming enormous quantities of neat rum and whiskey.

The night before we moved from Ecouvrie, the officers of our company joined us in the sergeants’ mess and we spent a convivial night with the rum jar. Tongues were loosened to such an extent by the fiery spirit that the officers forgot for a time that they were officers and Hardy for one let us see that he wasn’t looking forward with much pleasure to our expected scrap. He had won heavily at cards with the other officers and told us that he had at least £50 in English and French notes on him and that whoever found his body was welcome to the money. What a cheerful spirit to start a scrap in. Wanky Mitchell! Well we didn’t know what to make of him. He had a tendency for religious mania, but whether it was assumed or not for the purpose of working his passage back before the stunt we couldn’t say.

Jock Saunders, platoon sergeant of No. 2 had brought a water bottle full of neat rum with him and, being a typical Scot, drank the lot. I had a stroll amongst No. 2 Platoon during the night and came across somebody grovelling along the trench on hands and knees and making vain efforts to climb over the back of the trench. It was Jock and in one hand he had his rifle with bayonet fixed and all the time he was muttering ‘Where are the bloody Germans? Let me get at the bastards.’ I talked to him a bit and managed to get his rifle away from him, but off he went again. ‘Let me get at ’em.’ Just then Colonel Hutchinson came along looking for Wanky Mitchell and, of course, spotted Jock and the condition he was in. ‘Get four men, Sergeant,’ he said to me, ‘and keep this man under arrest.’ He told me the battalion was moving forward but I should have to stay there all night and look after Jock; I should hear from them in the morning. As soon as they had gone I found the best spot in the company sector, told one man off as a cook and, after a supper, we settled down for the night. Jock had dropped into a drunken sleep and kept moaning and shouting out all night. Sleep was impossible for me and I kept watch all night while my men slept like logs.

The night was fairly quiet with the exception of a few spasms of shelling down by Gavrelle. Just before dawn Jerry started slinging over gas shells in the dip about a hundred yards to our front. Over they came, six at a time. First came the familiar shriek of the shell through the air, then, instead of the deafening crash and crunch of high explosive, there was nothing more than a slight pop. There was no wind and, as it got a little lighter, I went forward to the edge of the ridge overlooking the valley and could see the gas as it hung like a pall over the little hollows in the ground. About 2,000 to 3,000 yards away I could see the church and village of Gavrelle, both of which looked in a pretty fair state from here.

About ten o’clock in the morning I was on the ridge again when I noticed two men coming towards me. One belonged to the Ansons, the other was a German and in a pretty bad way. I took them both along to our dugout and, as the cook had just made tea and a nice pudding, I gave them both a feed. I made the German understand that he was welcome to anything we had, but he wanted nothing but a drink of tea and that cold. He made signs that he was wounded through the chest and couldn’t eat. Just as he was finishing his tea a brigadier and lieutenant colonel of the Royal Field Artillery dropped into the trench and the brigadier asked me what party we were, what we were doing, and what the German was doing there with us. I made him wise and then he started talking in German to the prisoner and got information from him regarding his regiment, etc. He belonged to the 55th Reserve of Guards, the same lot that we were up against at Beaumont-Hamel. The brigadier then wished us a polite ‘Good Morning’ and took himself off. His colonel stopped behind to whisper a few kind words in my private ear. He said I ought to have called the whole party up to attention when the general came along. I told him I had saluted both when he came up and when he went away and hadn’t thought it necessary to bring the whole party up to attention. I told him even saluting in the trenches was not insisted upon in our lot. ‘Probably not,’ he said, ‘but this case is different, now you have a German prisoner with you, and it was up to you to show him that they are not up against a Rag-time Army.’ He was awfully nice about it and I gave him an extra-smart salute when he sheered off. They both left me with the impression of being two very pleasant gentlemen and altered my views a little regarding senior officers.

About half an hour later Colonel Hutchinson came along from the front and asked me how the prisoner (meaning Jock of course) was. I told him he was sober enough and sorry enough now. ‘Have your party all ready for moving in half an hour,’ he said. He was just going over to Brigade Headquarters and when he came back he would show us the way to our company. We moved off as soon as he came back and he led us at a fair old pace across open country which was in full view of Jerry. He kept away from the communication trench for about a mile, past derelict German field guns in concrete emplacements and ammunition dumps, past groups of dead men as they lay rotting on the ground. After a time he dropped into a communication trench of sorts that had been renamed Thames Alley by our troops. It was in a badly-battered condition with dead men lying about in all attitudes and various stages of mutilation and rottenness. Lewis guns, German machine guns, trench mortars, ammunition and bombs were scattered all over the place. I noticed that, although there were dead Germans in plenty lying about, our own dead far outnumbered them.

Thames Trench ended at Battalion Headquarters and the Colonel stopped there and told me to report at my own company HQ. He pointed out the way, and it lay over open ground as far as the support trenches and he advised me to run as we were very liable to get sniped. We were! Bullets were soon zipping amongst us and the advice to run was superfluous. With all my experience of warfare I had not acquired that pitch of courage or foolhardiness to walk calmly through a hail of bullets. In fact, I never have seen anyone like that yet, although I have read about them. I think that spirit is only acquired by the aid of other spirits, say a canteen of rum, or a bottle of whiskey.

Poor old Jock’s spirits had evaporated and he was quite as eager to run as the rest of us. We had about 300 yards to go to the nearest trench which lay along the near edge of the village, and I think we all made it in record time. We had an audience of a crowd of our men in the trench for the last fifty yards and they were splitting their sides at our frantic efforts to join them. We did join them and without mishap and I made my way to my platoon which was in a bit of a trench leading up to the front line.

I found Billy hard at work on a funk hole for Jim Hearne and himself, and I straightway joined him in making it big enough for the three of us. I scrounged some iron sheeting and logs of wood and we soon had a shelter that would stand anything up to a direct hit from a 5.9.

We had a busy time at night with the wounded men of 189 and 190 Brigades. Just by our trench was the uncut German wire, not like ordinary wire but like saws about half an inch wide and there were great masses of it, yards wide. Scores of our men were lying out in it and had been for three days. No one had made any attempt to see to them before and the poor devils who were alive were in a terrible condition. One poor lad had had a leg shot off above the knee and the stump was one mass of sepsis and gangrene. Nothing for him but morphia, and plenty of it. How the devil he had kept alive for three days and two nights I can’t imagine. Others died as we got them into our trench; just a few had hopes of life but very slender hopes. We made no attempt to tackle the dead; we left them for the pioneer battalion.

Our C and D Companies we

re in the line in front and some were holding the ruins of the village and both they and the Germans were inclined to be windy. Time after time the SOS lights were sent up, to be replied to immediately by both our own and Jerry’s artillery.

The night was pandemonium and the dawn was greeted with a terrific barrage put down by both sides. Sleep was absolutely out of the question and the dugout on which Billy and I had spent several hours of hard labour was only used on a few occasions when the shelling got too intense.

We were having a good few casualties and there was a steady stream of men from the front line. Just after dawn on the 26th a sniper from somewhere in Jerry’s line had picked off two or three of our chaps and we had a good look for him. Joe Woods spotted him at last in a tree on the Gavrelle-Arras road and four of us got on to him. He was pretty well covered with the leaves and branches but we had the satisfaction of watching his body crash to the ground. Some of us had got home on him. We accounted for a few more too before the morning was very old.

The Bosch was as badly off for communication trenches as we were, and his men had to nip over the ground in full view of us. It was just like shooting rabbits. There was Billy, Jock Baird and myself at the game and if one missed one of the others was sure to hit. We couldn’t help but laugh at the efforts of the Bosch. First he would nip over the back of his trench and start off over the open ground at a trot. A bullet from one of our rifles would make him sprint for dear life; another ten yards and he was down, most probably a dead German. It was coldblooded murder, but still it’s the same for both sides and some of the Germans managed to get back.

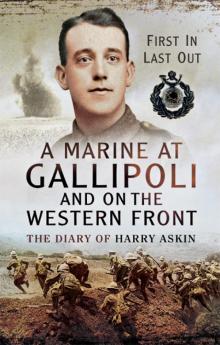

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front