- Home

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 9

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 9

An officer and six men of the Manchesters came along at night and went out at North Barricade to fetch in one of their men who had been killed some time ago. He did stink! Standing by for another bombardment, but thank the Lord, the wind was too strong. We sent off a few bombs from the barricade, but the wind carried them back almost into our own trench.

Stood to arms at 4.30 Sunday morning and think we might have been ‘standing to’ for a week, had not two chaps, one in our bay and one in the next, been killed. We were all stuck up on that fire-step for two hours and we must have looked like Aunt Sallies to the Turk. It got to a nice shooting light and one smart Turk took advantage and popped both these fellows off. They were dead as they fell off the step. Sergeant Owen came along, found out what had happened and played war with Captain Gardner, who should have passed word along to ‘stand down, carry on daily routine’ an hour and a half before. The captain went down the line next day sick. We got our own back next morning at ‘stand to’. Two or three of us waited with our rifles at the ready and just before it got really light a Turk climbed over the back of his trench. I fired and Jack Spencer fired. Perhaps we both hit him, we shall never really know that but I’m certain he never climbed out of another trench. Later in the day we picked out another nice spot for sniping. We could see where the Turks’ CT ran into his firing line and about twenty yards down was a bend where anyone passing was visible to us for about three yards. We spotted a big fat Turk and something caused him to pause at that bend. He paused just long enough for Jock Baird to hit him. He must have yelled because two more dashed down and tried to get him away. We got one of those and the other one dashed away again. I guess all the other Turks who used that trench went up and down it on hands and knees.

We were relieved at 5.00pm and went down to the reserve trench, which was blessed with the name of College Green. This was an old Turkish trench battered into the semblance of a sunken road and wide enough in places to turn a horse and cart round. There was plenty of room for a comfy sleep though, different from the firing line where the fire-step was anything from a foot to eighteen inches wide and that with an outward slope on it. I had a walk with Jack Spencer along this trench to the left and, about a hundred yards past our sector, came into a maze of old Turkish trenches, which had been shelled and battered until they looked like anything else on earth but trenches.

They had been taken by 29th Division on 28 June and had suffered terribly in the bombardment. The remains of Turks were still lying about all over the place, no attempt being made to clear them away or bury them. The whole place was littered with broken rifles, equipment, telephone wires, blankets and greatcoats. I shouldn’t like a revetting job with his sandbags; they held anything from one to two hundredweight of earth and it must have been an awful job getting them into position. All the print on the bags was in German. In some parts of the trenches he had run short of bags and had used blankets and greatcoats to fill up. Safety before comfort was his motto.

We could see where the poor old Turk had been crouching down under the parapet and in his little funk-hole during the bombardment and a shell had burst, filling up the trench and burying the lot. Arms and legs were sticking out from the sides and bottom of the trench, and if we touched them the clothing would drop off, revealing just a horrid-looking bone. Jack Spencer spotted a pair of very good boots on a Turk. ‘I’m having them,’ he said, ‘they don’t need boots in heaven’, and he took them off and changed them for his own. He was a queer chap. A short time before coming out here, he was an orderly to Admiral Jellicoe on the Iron Duke and got kicked out for being in a frightful state of intoxication whilst escorting the Admiral’s wife to somewhere in a motor car.

I was jolly pleased to get away from that hell hole. The whole place stank of death and disease and everything was swarming with horrid black files and grass-hoppers. We were really hunting for firewood but had no luck. We spotted some barbed-wire stakes just over the top and went out to pull a few up and could see where several dead Turks had been hastily dragged into a heap, oil poured on them and fired. They were only half-burnt though and the stench from them was awful. We lingered out there a little too long and a Turkish sniper got busy. Two or three bullets whistled unpleasantly close to us so we got back at the double.

Went out again on the sapping job at night, for four hours, and had a few bursts of rapid while working. We had nothing to do the following day so had another walk through the ‘shambles’. Thought I might get a few souvenirs, but couldn’t bring myself to touch those dead Turks. C Company, who had relieved us, sent a few bombs over at night from the Northern Barricade and one burst in the catapult, wounding five of our men. Relieved by the Hawkes early on Tuesday the 7th and went down to Rest Camp. Had a bathe in the sea, a clean change and felt A1.

We did fatigues for four days, first making winter quarters for the corps staff on the beach, second building a pier on Y beach, the third and fourth days with a sanitary squad at divisional HQ, shovelling a big stack of dry horse manure into a deep pit. Both those days were very windy and I think I swallowed nearly as much manure as I put into the pit. Anyhow, on Sunday I felt bad and thought I was going to touch for dysentery or jaundice. Both complaints were prevalent and it was pitiful to see the men with dysentery. They could hardly crawl about and had no hopes of getting sent away from the peninsula or even to field ambulance unless they were just about dying. There appeared to be absolutely no method of preventing or treating the disease in that awful place. It was a sickening sight to see the poor devils as they crawled on hands and knees to the latrines, lying there for hours, in many cases all through the night. My chum Mick Smith had had it bad, but the doctor sent him away on the Sunday. I never expected him to get better.

I felt bad on Monday, but didn’t report sick as there were no fatigues on. We went over to 3rd Field Ambulance (3 FA) in the afternoon to be inoculated again for cholera. When we got back the company was being paid out and I drew 10/- (50p). What on earth they paid us for I don’t know and didn’t care much then. Fancy giving us 10/- in that wilderness?

I crawled down to the doctor’s shop on Tuesday morning. I had a temperature of 101.2, so I suppose Jimmy Ross (that’s our pet name for the doctor) thought I was ill. He excused me duty and ordered me milk diet. I didn’t waste any energy thinking where I was to get the milk from. All I wanted to do was get down and sleep. Some of the chaps bought some eggs from a Greek on the beach and tried to tempt me with them but I couldn’t face anything. The doctor put my complaint down as pyrexia2 on Wednesday. Don’t know what that is. The battalion went up the line after tea but I stayed down along with about fifty more sick, lame and lazy. We all had orders to report at 3 FA in the morning for treatment. There was a frightful storm all night, rain, thunder and lightning but I slept through it all. I was lying in about two inches of water in the morning and, as soon as I made to get up, all the water that had collected in my waterproof sheet – and there was at least a gallon – came down on me, drenching me through. Nothing mattered. They packed me off to the beach CCS from 3 FA and from there to the hospital ship Valtivia, where, thank the Lord, I was able to undress and get into a clean bed. And there I stayed until we reached Lemnos on the Saturday afternoon. I felt a bit better then and went up on deck. I had something to eat on Sunday, the first for a week and then managed a shave.

I was taken on the 21st to the 1st Canadian Field Hospital and stayed there till the 29th, receiving better attention and food than on either occasion in Egypt. There were some real jolly Canadian nurses there and I felt sorry when the time came to move to convalescent camp. Once there the hardening process commenced and I was pushed with seven more chaps into a bell tent. It certainly had floorboards but they were damned hard after a soft bed. All the other fellows in the tent were of different regiments and absolutely different natures and, although arguments got rather fierce about the merits of our respective regiments, we got on very well together. Most of our time we spent playing bridge but lif

e there was rotten. I think that convalescent camps are instituted by GHQ solely for the purpose of making wounded and sick men so fed up that they are only too glad to rush back to the fighting. I know that my short stay in the camp had been far too long. I was put on sanitary squad fatigue from getting in camp to leaving it. The work consisted chiefly of emptying latrine buckets twice a day, and digging great pits in the hard ground to bury the contents. Quite a nice steady job for a chap who had just been dragged from the ‘edge of beyond’.

I had a few letters the day before leaving convalescent camp. As a matter of fact there were forty-three and I hardly knew how to begin on them. One night, while in camp, we had a violent wind and rain storm and had to dash outside with only our shirts on. We could feel all our tent pegs giving and by the time we got outside they had given and we had to hang on like grim death. Half the camp was down by morning.

It was 15 October when I went to the RND detail camp and it was no easy job getting away from there. There was plenty of work but we had a certain amount of freedom and a little pay, so I managed a run through one or two of the villages. These half-Turks-half-Greeks were realising one of the effects of the war – easy money by fleecing the British Tommy.

I left Detail Camp on 21 October and embarked on the Brighton, a big minesweeper. The voyage to Cape Helles was awfully rough, waves washing right over the boat nearly the whole way. The weather seems to have broken up and I reckoned we were in for a rotten winter.

Landed at dawn on W beach and went straight to the battalion. Joined up with the same section and found them in new quarters. They were supposed to be winter quarters but the dugouts were only partly finished. All the camp was laid out on proper lines and all work carried out under supervision of the engineers. Dugouts were twelve feet long, six feet wide and four feet deep, and we were to have sheets of iron to put on the top. I wonder! No one was allowed to walk about on top as we had five-feet trenches connecting up all the dugouts and lines. The Turk might know we were here if he saw us walking about.

Just a few words about the section. Captain Pilgrim in charge, a real decent chap and a first reinforcement. He was wounded pretty badly in their little stunt on 25 June and had only lately rejoined.

Private Daniels, long-service marine and just reverted from corporal. He had just done seven days’ field punishment and couldn’t get over it. He got wrong with Major Tetley over some Turkish binoculars and of course went under. He was talking about getting back on the signal staff again and good luck to him. We all hoped he would get back; he always had a moan on.

There were Jock Baird and Tommy Barlow, old chums, and a bird by the name of Clayton. All the chaps nicknamed him Kelly and he was the dirtiest specimen of a marine that I had ever struck. He was lousy. They say a chap is never really lousy till they come out of his lace holes. Kelly was beyond that. He made me shudder when he came near me. He was one of the original Plymouths and was badly bayoneted in the scramble to get off the peninsula on 26 April. The back of his neck was covered in wounds, some of which kept discharging, owing, I supposed, to the filthy state in which he kept himself.

I shook down alright with them all and they shared rations and parcels for the first day. They said it was a lucky dugout for parcels and hoped now it would be more lucky.

It rained all the first day and my new WP sheet came in handy. It kept the dugout fairly dry.

Up at 6.30 next morning, improving dugouts and drains. At it till noon, then from 1.30 to 6.30 on fatigues at the bomb school at the beach. We only had two shells over all day and they pitched about ten yards from our line. About ten men were leaving the battalion every day through sickness, some of them just worked to death. It was nothing but dig from getting up to getting down. Our new CO, Colonel Hutchinson seemed keen on it. If we weren’t digging our own camp, we were doing for divisional HQ or brigade HQ.

We were all inoculated on the 26th for cholera and the following day went up the line. I was let in for the section as Corporal Daniels had picked up his two stripes and had rejoined his signal section (for which Allah be praised). A platoon of London Fusiliers was attached to our company for instruction in the line. As they were unable to bring their big sisters with them from Malta (where they had been since 14 August) we had to carry their blankets, fetch them water, let them have our funk-holes to sleep in, and carry them about generally.

We were filling sandbags all the first morning, in the M Barricade and revetting fresh traverses in the F line. Told off for duty in Sap 9 at night. This was the new firing line and ran from N[orth] Barricade to the Manchesters on our left. This was the little sap that Mick Smith and I worked in before I was bad. It was a fine trench now but awfully near the Turks, only about sixty yards in some places. We had a new chap with us, Sergeant Jeffries, a pre-war Bisley man and crack shot of Plymouth Division. He arrived with two rifles, one fitted with telescopic sights for fine sniping. He came in Sap 9 the first morning, got on the fire-step and took a few pot shots at nothing in particular. A good shot he may have been, but he had a lot to learn about the kind of shooting that was done out there. It’s a case of one round, one position. It was about his fourth shot and as soon as he had pressed the trigger his hat flew off. One of Johnny’s fairly decent shots had beaten him. The bullet went clean through the front and back of his cap, taking with it a few of Jeffries’ remaining hairs. He never sniped from Sap 9 again.

We had a crazy way of working things at night, Captain Gowney’s idea again. Everybody did half an hour on watch, and was down half an hour, and every man during his half hour on watch had to fire at least five rounds. Most of the bullets, from the sound of them, would just about hit the top of Achi Baba, about two miles away. Usually the half hour up would seem like hours, our heads nodding, our eyes half closed and our minds a complete blank. Had it not been for the five rounds we had to fire we should have gone to sleep standing up.

The half hour down went like a flash. We no sooner appeared to drop off than our opposite number was shaking us, ‘your turn up’. ‘Go on, I’ve only just got down,’ we would say. Sometimes it would need the corporal or sergeant on watch to induce some of the fellows to get up. They were awfully long nights too, and it was frightfully cold, especially the hour before the dawn and ‘stand to’.

We had a Sergeant Major Cutcher in charge of our platoon, and a dizzier old bird I’ve never struck. He just daren’t put his head above the top and he went off something alarming at me for looking over the top without using the periscope.

We went down to the reserves on the Friday afternoon and at night went out digging a new trench. It was all top work and the whole time bullets were whizzing by us or going plop, into the ground by us. No one was hit. The whole area of ground that we were working on was littered with dead men, and we had to move several of them before we could get on with the work. All sorts were there, Scotties, English, Indians and Turks. One chap we moved was a major. Gowney got another brilliant idea: we were to have a big party out, collect all these dead and burn them with some sprayers and chemical stuff. One party did go out, but all they collected was souvenirs. As soon as they tried to lift the dead they dropped to pieces.

Johnny shelled our line pretty heavily on 31 October. He had got some 4-inch howitzers by then and was getting pretty accurate with them. We moved to Sap 8 on 1 November. It was very decent there, and about 150 yards from the Turk. A dead man was lying just in front of our parapet and when Johnny kept hitting him with a bullet, which was pretty often, the stench was awful.

We had a few spasms of rapid and on Tuesday night the Turk shelled us with shrapnel and sent over a lot of bombs. Old Bob Trevot, our sanitary sergeant, woke up at ‘stand to’ in the supports and found out that he was wounded. A shrapnel ball had gone through his leg. Volunteers were wanted for a wiring party at night. Jock Baird and I went out with Sergeant Douglas and pulled a few coils of concertina wire out and pegged it down. Then there were a few chevaux-de-frise to be put into position. It was a quee

r sensation being out in no man’s land at night with firing going on all around and lights going up suddenly from the Turks’ trench. Everything was like day then and it was policy to stand still. It made me feel like dropping down for cover and you felt certain a Turk only fifty yards away had just got a fine sight on you. I expect the Turks were like most of our fellows though; as soon as a light went up, they got down.

The 1st RM Battalion put some wire out one night – just chevaux-defrise – and never anchored them to the ground. Next morning the wire was in front of the Turks trench instead of their own. We were relieved at 5.30pm on the 3rd and went down to camp again. We had a stand-off on the first day to get cleaned up and I ran into a square number as company clerk again. There was no clerking to do, I just had to fetch the company’s mail every day if there was any, serve rations out to platoons and keep the CSM’s and QM Sergeant’s rifles clean; they were a drunken pair, especially CSM Chapman. He came out with us in Portsmouth Battalion, as a bugler, was made corporal of the band at Port Said (where it died) and colour sergeant after Gaba Tepe. He won’t get much beyond that because his best friend, Jacky Luard our old colonel, has gone west. The Hawkes had a little stunt on the Saturday night. They advanced from both barricades, but only succeeded in making headway from the Southern. From there they advanced about twenty-five yards and dug in. They had several casualties.

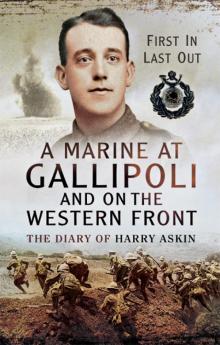

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front