- Home

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 5

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 5

I got out of that and a bit farther down came across a big Australian with a water bottle full of rum. He gave me a good drink and I felt heaps better after and thought for a time that a wound or two was nothing. I felt no desire to turn back for another go, however. Another Aussie called me into a funk hole a bit later on and told me to rest a bit. There was another in the hole and I asked the first chap if he was asleep. ‘No,’ he said, ‘he’s dead.’ I didn’t stop there long.

I was followed all the way down the gully by shrapnel. The Turks were searching the whole place and, while dodging one shell, I tripped over a ground wire and fell onto my left shoulder. Farther down, while running from another, I ran my wound straight on to the branch of a tree. Swear? Never so much in my life. I never thought I should reach that dressing station alive. Just before I reached the bottom of the gully I saw an Indian leading two pack mules up the gully. He got about twenty yards from me when a shell burst and killed all three. I reached the dressing station at last but what a state it was in. The wounded were waiting in queues to be dressed and the station itself was full of wounded and dying men, most laid out on stretchers, all who could groaning out curses on the Turks. There were several doctors, naval and Australian, all of them performing their duties in a dazed manner. I don’t think they had slept since landing. I looked round amongst the wounded and saw several of our chaps that I knew: Captain Stockley of A Company with one leg shattered; Sergeant Major Wingfield terribly mauled about and several others. One chap was brought in and as soon as the doctor looked at him he told them to take him outside and put him under the cliff with the others. The others were dead. Scores of them. My turn for dressing came and the doctor started probing and poking. I don’t think he knew what he was doing. In the end he said he wouldn’t bother taking the bullet out there, perhaps they’d take it out on the ship. Thank the Lord for that! I was eager to get away from that accursed place. I was sick of seeing dead and dying men, tired of hearing moans and cries, and sick with the smell of blood. I was covered with it and everything was covered with it in that dressing station at Gaba Tepe. Stretchers and men soaked with it and even the sand was red with blood.

I got in a boat at last with a crowd of others, not too badly wounded, but all utterly fed up and exhausted; not a smile in the whole boat. We were waiting for a picket boat to take us in tow but just before it arrived the Turk started shelling the beach and we got the contents of another shrapnel round in our boat. An Aussie sitting next to me was wounded again in the back. ‘God!’ some of us exclaimed, ‘Aren’t we to get away now?’ We were towed away though, and the midshipman in charge of the tow didn’t look more than sixteen years of age. Quite a boy, but I bet he and his mates had had a tottering time round the beach for a few days. They hadn’t even the chance of hitting back. We reached the hospital ship Gascon and went on board. Sorted out at the top of the gangway according to the severity or otherwise of our wounds, we were told off to different wards.

I had my wound properly dressed and cleaned and then passed out. I hadn’t even time to realise that I was on a soft clean spring bed and that a real Englishwoman, young and nice, had dressed my wound. I went right away and must have slept at least twenty hours. Woke up about noon on the 4th but felt far from well. We were still lying off Gallipoli and taking on stretcher cases. Had a stroll round the ship and found it full with lots of our chaps on board. Poor old Wingfield was there in the same ward. I had a talk to him and told him that I’d seen him roll past me down the side of the gully. He said a lump of case shelling had hit him in the ribs, smashing about four or five, and he had a few more wounds besides. It was difficult to see anything but bandage. He told me that it must have been Lieutenant Sanders who followed him, as he had been with him.

Heard that the colonel was wounded and on board the Gloucester Castle, Major Hoskyns Abrahall killed, Mr Erskine killed, Dougherty wounded, and several others killed and wounded. Majors Armstrong and Clark, and about three other officers, were left with about 150 men.

We had on board English nurses, doctors and Hindu attendants. We dropped about eight dead over the stern about 6.00pm. The Gascon sailed about 9.00am on the 5th. I felt much better and spent most of the day on deck reading. We had a lovely voyage to Alexandria and arrived on the Friday morning. Every evening about six the ship was stopped and several dead men were dropped into the sea. We buried forty-one men altogether on the voyage. Disembarked and entrained on a hospital train and had a steady run to Tanta, about halfway between Alex and Cairo. Batches of men were taken off at various towns down the line, according to the accommodation of the hospitals. About fifty of us were taken off at Tanta. We were taken in open carriages to the hospital and it looked as though the whole town had turned out to greet us. The streets we drove through were lined with natives and native soldiers were having a rough job keeping them back in places. Some people had a queer way of showing their feelings. As we passed up one narrow street we were pelted with stones.

Got to hospital about 7.15pm and gave our particulars for about the twentieth time since being hit. Seized immediately by two greasy-looking Arabs who fairly ripped the clothes off me, I was shoved under a hot shower and scrubbed with more energy than feeling. Wounds were treated as sound flesh and how the devils delighted in it. I felt an immediate and violent hatred for Egyptians from that time. Dressed in native clothes after the bath and waited my turn for the doctor, an Egyptian, fat and jovial, who had practised in Paris and London and spoke English fairly well. He had a look at the wound, then said ‘Sit in that chair’, so I sat in it. He got a knife and slashed me about an inch where the bullet was, then got a pair of forceps, gave a pull and the bullet was out. He informed me that it hadn’t hurt. I can’t say that it had hurt much, very much like having a tooth out. I wanted the bullet, which was a shrapnel ball, but the doctor wanted it too. He said it was the first he had taken out of an English soldier and he wanted it for a souvenir. ‘We both have souvenirs,’ he said, ‘you have the wound, I have the bullet.’

Got to bed after a supper of goat meat and macaroni, served up by a French Sister of Mercy. The sisters were quite ancient and couldn’t speak a word of English, but were very nice. A batch of French soldiers was already there; they had been wounded in the landing at Kum Kale on the Asiatic coast. There were two old marines and seven Australians in my ward, none seriously wounded.

We had lots of distinguished visitors to see us, including the Countess of Caernarvon, General Maxwell and Prince Alexander of Battenberg who was kind enough to say he hoped we should soon be back to help the others. I wondered if he’d any idea what sort of hell it was and if he’d like more than one dose.

I had a tottering time with the mosquitoes. They bit me in every possible place and my face was a mess. I was unable to shave for over a week and all that time I was anxious to try a new razor that a charming young lady had given to me. I had lost my own razor when I threw my gear away.

The English people were fine and would get us anything we wanted. They couldn’t do much for us in the food line, though. The good people in charge of catering and cooking had some crude ideas about feeding Englishmen. Natives were more in their line. My wound healed up fine, but I didn’t feel very grand. Perhaps the weather was too hot.

Sunday brought lots of visitors. The natives who were anybody were allowed inside and all the French people came. The town band came too, but I liked that best when they were smoking. I got very interested in one of our attendants: one of the worst-looking specimens of a low-class Arab that I’ve ever seen, he selected a spot in the garden in front of a little water-tap arrangement, took a prayer mat from his pocket and knelt down on it, then started salaaming to Allah. The performance included dabbling his hands in water and various other motions of ‘tic-tac’. I suppose after that he would go round the wards and steal something. A photographer came one day and took each ward. Ours turned out a treat so I sent one home.

My wound was better by 19 May and I was able to dis

pense with bandages. I was fed up with hospital and eager for a glimpse of life other than that to be obtained from the roof of the hospital. A specialist came up from Cairo on the 21st and marked me off for convalescence at Alex. The draft was to go on the 21st, Whit Monday, but I managed to get a touch of fever on the 22nd and thought I should just about manage a draft for Heaven, or wherever marines go. I nearly knocked on the Saturday and the mercury nearly pushed the top off the thermometer. The old doctor came to see me several times during the day and, about 6.00pm, left me with a soft white tabloid of quinine. I had no idea how to take it so chewed it well, and I thought I should never forget it. What a change in the morning though! I was up and about and ready for the draft, but the old man wouldn’t hear of it. A cinema show was arranged for us in the grounds at night with iced drinks and a few extras. That was to keep up the spirit of Whit Monday I suppose. One fellow died on the 29th. He had been wounded in the head and had then contracted Erysipelas. He had quite an impressive funeral. Another was taken away to the isolation hospital with the same complaint.

I had a fearfully monotonous time up to 2 June. Sat on the hospital wall that day, along with two big Australians, having an argument with some natives in the street below. The old major-domo, or whatever he was (boss of the native attendants), came along and told us to get off the wall. Of course we replied with something polite in plain English, upon which he seized the ladder which one of the Aussies was standing on and pulled it away. I never saw such a hit as that Australian gave him; he went down as though he was shot. Several more natives rolled up and we had a regular mix up for about ten minutes. Then we faded away. The doctor came round later and with help from some of the natives and some French soldiers, picked these two Aussies out. It wasn’t difficult because their hospital clothes had been ripped off their backs and what they had on was covered in blood. There was hell to pay; both warned off for draft and a report sent to their depot. That didn’t bother them any though. I don’t know why I wasn’t clicked; perhaps they thought I wasn’t big enough to be awkward. I was down for draft though.

We drew our old clothes and left Tanta at 9.00am on the 3rd and arrived at Alex by 11.00am, then took the tram to Mustapha Barracks where nearly all base details were, about three miles from town but easy to get to. I was detailed off with the marines but didn’t strike any old chums. Saw the MO in the morning and was passed A1, drew a rifle and a new set of equipment, clothes and other kit and was busy all morning getting it fired up. I had heaps of letters from home and hardly knew where to begin. Bob Hester joined up from Cairo. He hadn’t been wounded and I don’t think he knew how he’d got away. Said it was rheumatics or something like that. He had come away on the Cestrian, an old cattle-boat and had fed on bully beef and biscuits during the voyage. Poor old Billy George had come on the same ship but had died.

Paid 112 piastres (£1-3-0d/£1.15p) on the Saturday, so felt entitled to a run downtown. Alex is a lovely place with some splendid buildings and lovely shops, especially in Sherif Pasha Street, which seems to be the main thoroughfare. I found one shop where we could buy lovely French pastries, ices and cool drinks and I’m afraid I nearly made a beast of myself. I think I could be excused that though after the stuff I’d eaten lately. Did a two-hour route march on the Monday morning and wasn’t it hot! Saw the MO afterward; he passed me fit for active service again. Went downtown again and had a last tuck in at the pastry shop and an hour in the casino.

Embarked the next day on the Cardiganshire with about 140 RN details, a decent solid-looking boat of about 8,000 tons. Lots of troops on board: details of the 29th Division, Australians and some Egyptian engineers. Steamed away about midnight. I made my bed up on deck as usual and enjoyed the voyage, although it was rough the whole way. It bucked me up fine and made me feel fit for anything.

Arrived outside Lemnos on 11 June but didn’t get in until the following morning and found it full of ships and troops. Heard news of the Collingwood and Benbow Battalions, who had come out to complete the division. Two days after landing, they were used in a big attack on Achi Baba on 4 June. Collingwood had over 800 casualties and Benbow between 600 and 700. The battalions ceased to exist and those who were left reinforced the other naval battalions.

All our division had been transferred from Gaba Tepe to Cape Helles. The Australian details left us the first day for Gaba Tepe. Two hostile aeroplanes came over on the Sunday flying very high. Our ships blazed away at them with no visible effect, except that they soon made off. A transport berthed up alongside us, full of Sikhs and Gurkhas. The Sikhs are fine-looking men, tall and well built, and take as much pride in their hair and appearance as a woman. They even keep their beards in pins overnight. The Gurkhas are their opposites; short and stumpy and care for their appearance as much as a frog does. Ugly as sin they are. They did their own cooking on open fires on deck. Chapattis or pancakes were the chief article of diet. The Egyptians landed on the Sunday and on the Monday all the Indian troops left the Ajax. There appeared to be about 2,000 of them and they went up to Gaba Tepe.

Chapter Four

15 June – Cape Helles

Tuesday morning saw a move for us. We were transferred to the Whitby Abbey, a minesweeper, and left harbour about 8.00pm. Arriving off Cape Helles about midnight we were taken to the River Clyde by a trawler. My! Didn’t she roll. She was just like a tub and I was glad to get on to the firm decks of the River Clyde. This was the ship that had been run ashore on 25 April, full of Dublins and Munsters. As soon as she grounded they were to pass through doors in the ship’s side, down the gangways and onto the shore. It made shivers go down my spine as I thought of those poor devils cooped up on that ship with nothing but certain death before them. The venture would have been a complete success had it not been for the inevitable mistake. Just that little miscalculation, and instead of grounding on the beach ten yards from cover, she ran aground on a reef about fifty yards offshore in deep water that the Turks had wired. Some of the Irish wouldn’t wait for lighters to be moved into position but jumped from the doors into the water, pack, rifle and everything else on. Their fate was obvious. What few reached shallow water got caught on the wire and simply shot down. We passed a grave on the beach with 200 Irishmen in it. There were lots more graves, and scores of bodies had not been recovered from the sea. What few were left from the two battalions were joined together and called the Dubsters.

We slept in an open air camp till dawn under the shelter of the fortress castle of Sedd-el-Bahr. Breakfasted on Maconochie’s and biscuits, nothing to drink, and as soon as our respective guides came we moved away. Had a good view of the castle and village, all in ruins. We moved left along the beach, past the battery of 11-inch guns that our ships had smashed, then up to the first rise that had cost so many lives. There were piles of food, stores, ammunition and fodder for the horses, just stacked up anyhow. Hospitals and clearing stations were rigged up on the beach, too. On top of the rise was a new cemetery with hundreds of fresh graves neatly laid out, all British. Nearby was an old Turkish burial ground with a few stone crosses and pillars standing up. A splendid view of the country could be obtained from the top. About eight miles to the front could be seen the Achi Baba ridge running from coast to coast and looking more like the head and shoulders of a man. In between was a valley or a basin with olive groves, vineyards and old-fashioned wells dotted about all over the place. On the right by Morto Bay could be seen the remains of several big houses and an aqueduct, and to the left, about five miles away, was the village of Rhothia, looking from here fairly intact. The very conspicuous thing was a row of six windmills to the right of the village. The Dardanelles flowed on the right and on the left was the Aegean.

Over the straits one could see the coast of Asia and the plain of Troy where a battle was fought a few thousand years ago for the beautiful Helen. I didn’t see many beautiful Helens knocking around. It appeared far more civilised than the country round Gaba Tepe; the whole place looked peaceful, with no sounds or sig

ns of fighting.

Walked about a mile and a half across country, over bits of trenches, funk holes and wide dugouts for stabling the horses. Passed hundreds of troops bivouacked in holes in the ground about three-feet deep and large enough to hold from two to six men. Found Portsmouth Battalion at last and reported at the orderly room, a dugout rather larger than the others and covered with a tarpaulin.

Told off to No. 8 Platoon (Sergeant Spicer) No. 2 Company with Captain Gowney in charge. The battalion was down to two weak companies, but had just been reinforced by a new company from England under Major Grover. Major Clark was in charge of the battalion with Captain Chandler, just out, as adjutant. Had invitations from several of the chaps to dig in with them, so Bob Hester and I dropped into the hole that required least digging. There was old soldier Robinson and two more fellows in it. Everybody was feeling downy. It appeared that a big gun from the Asiatic side kept sending big shells over, something like a 10-inch, and only the previous day had dropped one amongst seven of our fellows. Tom Watts (an old friend), filthy Joe Hartley, the cook, who had never washed since leaving the ship, an MG corporal and four more men were all talking about twenty yards from the galley. Tom had an arm blown clean off, one chap was killed by the concussion, hadn’t a scratch on him, the MG corporal and another were blown to bits, which were picked up from all over the camp and put in sandbags. Only Joe Hartley escaped unhurt. The fellows told me that old Tom Watts walked straight over to the doctors carrying his other arm. He just said something cheerful, ‘Could he stick the blurry thing on again’, and then went off into unconsciousness. He was hit about the head too. That little turn, along with a few more 10-inch shells, had shaken the chaps up a bit.

Up to about 9.00am I had heard no signs of fighting but I hadn’t much longer to wait. The chaps in our hole had told me that our place was the worst in the camp. A road ran through our camp and all the transport from the beach to battalion dumps and batteries passed along it. Our dugout was right alongside the road and just at the spot where the Turk dropped most of his stuff. I was crossing the road intending to find some old chums, when I heard the old familiar sound of shells rushing through the air. Action left me, I couldn’t move, and took no notice of the other chaps yelling to me to run and get down. The bursting of four shrapnels put action into me, though, and I could feel the bullets whizzing past me as I dived across the roadway. I have hazy recollections of turning about three somersaults, then finishing up in a small dugout on top of Harris, an old roommate at Forton. Talk about ‘atmosphere vertical’. I had it.

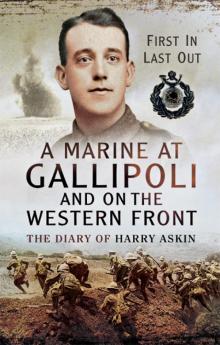

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front