- Home

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 29

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 29

He said that whatever happened we mustn’t let it get to the Colonel, or there would be serious trouble about it; Marsden’s wife might lose her pension through his folly. Not only his wife, but the mad idiot had five kiddies too. Curse the bloody rum!! There was one certainty about this stunt as Hardisty said. There would be no medals.

I turned in after that for two hours but sleep wouldn’t come. For one thing, I was too exhausted; for another, I couldn’t get Bill Marsden’s wife and kiddies out of my mind. The whole thing was like a horrible nightmare. The day passed off fairly quiet and, with finding the men plenty of work to do, I managed to shake off the memory of the morning.

We were out wiring again at night but it was a scrappy job. Our guns put up a strafe at 9.00pm and the Bosch retaliated, making both a mess of our new wire and our trenches. Luckily there were no casualties. We managed two hours’ wiring between 10.00pm and twelve midnight when the Bosch opened up again with 5.9s and a bit of shrapnel. We could find no reason for it whatever, but then the Bosch was a very uncertain beast and his ways were very strange and sometimes passeth understanding.

I have an idea that Jerry was holding his first and second trenches with only a handful of men, especially in the daytime. At night I think he had pretty strong patrols working up and down the line, and these sudden strafes from his guns were just to give the impression that he was all about and in good strength.

Two more hours wiring between 1.00 and 3.00pm and then a rest until ‘stand to’. Orders along to get ready for moving down as soon as we stood down and the Hoods relieved us about 5.30am on 17 September. Billy and I, along with Billy Black, were bringing up the rear of our company when, halfway down new Foxy, the Bosch sent over a whizz-bang which burst in the trench just behind me. The force of the explosion lifted me off my feet and sent me with a crash into my two chums; we finished up at the other end of the traverse in a tangled heap of cursing and very scared humanity. It might have been a horrible catastrophe for the British Army, and a feather in the Germans’ cap: three of the smartest sergeants in the Army nearly out at one smack. If the German High Command only knew how near it was, they would give that gun’s crew Iron Crosses as big as frying pans. Three very frightened sergeants ran like hell when they untangled themselves and found out they weren’t hurt. Fancy getting almost laid out when we were off for a rest.

We were some time catching the company up and Mr Downey was just ready for coming back with a party to gather up the pieces. He said they’d look well in Kensington Museum. We thanked him nicely for his kind solicitations on our behalf and made our way steadily down to St Aubin, near Arras.

Chapter Thirty-Three

September 1917 – Now for the Salient

Billets at St Aubin, any sort of billets, but very acceptable after the open trenches. We slept like tops, but I woke up in the morning feeling stiff and sore with great bruises all over my body from the effects of the shell. We had hot baths, clean clothes and a good spruce up, then Captain Ligertwood, who had only recently taken over our company paid us all and with 50 francs in my pocket I felt like facing a few of the terrors and pitfalls of the Arras estaminets. I formed one of a very jolly party that night and we almost shook the ruins down with our songs.

The next day was a stand easy and we began to look like soldiers again. Clean buttons and badges, boots shining and clothes brushed as clean as we could get them. Marched to Ach on the 20th and then on to Frevilliers the next day to some decent billets, with plenty of decent straw to bed down on. Found out we were only about four miles from Ohlain and set off for a walk after drill had finished to see if the old place was still there.

It was a beautiful evening, visibility good for miles, and all the woods around were showing their autumn tints, every conceivable shade of brown and green. A more peaceful scene it would be hard to find. I watched four of our fighting planes take off from one of the aerodromes and fly calmly on their way to the line for a spell of dirty work. They looked like four huge birds of prey sailing majestically along with the bright blue of the sky all around them. I stood still for five minutes drinking in the beauty of it all. One couldn’t imagine trouble, but it was there.

Suddenly one plane dropped out of line and turned his nose round and made for earth. All at once his nose dipped and he crashed into the corner of a field and almost at once burst into flame. The sense of peace was shattered, and one realised again the horrors of war. Sudden death, and, perhaps for the two poor devils in that plane, worse. Lingering death, but nevertheless, death, far better than getting smashed up body, mind and nerves and then not to die. That’s the only thing I feared, to drag on year after year in that horrible condition. Away with such horrible thoughts. A horse and trap came driving up to me and the only occupant was a French girl. She pulled up when she got to me and wished me a polite ‘Bon soir, Monsieur.’ ‘Bon soir, Mademoiselle Jeanne,’ I replied. She stared hard at me and I could see recognition come to her. ‘Ah. Le petit Corporal Harry,’ she said and motioned to jump up beside her. I felt quite honoured, to be recognised by Jeanne after all these months. Hadn’t poets of two Armies sung her praises, colonels and brigadiers fought over her, Jeanne of Ohlain!

It was a pleasant ride to Ohlain and we carried on a conversation as well as we could. She wanted to know how Monsieur Billy and the big Charlie were. She was quite touched when I told her about poor old Charlie and some of the others. Ohlain was full of Canadians, most of them French-Canadians, and they were a noisy crowd and Jeanne’s place was crowded with them. There were cries of delight when she came in and I came in for a few curious looks from some of them. She took me to see her mother who clucked over me like an old hen, and I had to give an account of myself and the others. All this over a bottle of their best champagne. Wonderful stuff, and I soon felt all aglow. I didn’t stay long because I had a long walk back and the night was pitch black.

I hadn’t been walking long when I thought I heard footsteps behind me, but could hear nothing when I stopped. There they were again though as soon as I started and they kept pace with mine whatever speed I kept at. My nerves weren’t very steady and the champagne had gone to my head a bit and I began to imagine things. All sorts of weird thoughts kept flashing through my head and I gripped my loaded stick tightly by the thin end. The footsteps were still there, getting no nearer but keeping pace with mine. An empty and forsaken village loomed up out of the blackness and I glanced nervously about me. Not a light about, not a sound but the steady tramp, tramp of the footsteps behind me. Just on my right was a graveyard and just beyond, looking huge and ghostly in the blackness, a church with a big square tower. Suddenly, a horrible bloodcurdling shriek rang out, and the marrow in my backbone froze and I stopped dead. Any second now I expected something to grip me and beads of perspiration stood out on my forehead.

I managed to look up at the church tower and, dimly, I saw the figure of a large bird fluttering around, which, in a second or so, gave out another horrible shriek. An owl! I took off my cap to wipe my forehead and felt something jingle in the cap. A small piece of chain with a steel ball on the end. I remembered then taking it off a dead German and pinning it on the lining of my cap. This thing had been banging on the leather band every time I put my foot down and accounted for the following footsteps. I stood there for five minutes and cursed myself. I called myself everything I knew about and then made a few more up. When I reached my billet I sat down and wrote home for a bottle of Phosferine tablets.

The days following were now full of drill, discipline and red tape, and I was busy for several hours trying to knock a bit of shape into my platoon. And it was a task. Most of the men had forgotten all their drill and discipline; up the line and down are two different and distinct things. I hadn’t much help from my platoon commander, Mr Downey. He looked all right certainly, and had a lovely pair of light-coloured breeches, but his knowledge of drill was practically non-existent. Our captain was keen though on getting the company up to concert pitch for the n

ext stunt, somewhere near Ypres as rumour had it, and, as Captain Ligertwood was liked by everybody, we all went to work with a good grace and the company was fairly happy.

At drill on 26 September when Dick Howarth came along and told me that the captain had put my name through to the colonel for a commission. ‘Would I go?’ the sergeant major asked. ‘How long does it mean in Blighty, Dick?’ I asked. ‘Oh, about six months,’ he said. Needless to say, I was on it like a shot. I had to go along to the colonel, who talked to me like a Dutch uncle and told me it depended on the brigadier. I should have to see him and satisfy him that I was fit to be an officer. I was all excitement and eager to be off, but of course had no idea when I should have to go.

On the 27th we started a musketry course to qualify for our good shooting allowance and I managed to get 89 out of a possible 100. Made sure of my penny a day at all events; dated back for nearly three years it meant a nice little sum in reserve.

I filled in an application form for a commission on the 27th and the following day passed the doctor and saw the adjutant, Captain Newling. On 1 October I had to go to Chelers to see the brigadier, but there was nothing very terrible about it. He was very human and nearly nice. He had all my particulars down on a paper and only asked me a few questions. Then he told me I would have a hard task to pass the exams at the Cadet School as they were very severe but that, according to my reports, I should have very little to fear from the practical side, but must swot up on infantry drill, and King’s Regulation, etc. And then, with a ‘Good luck, Sergeant’, he dismissed me. There was only one other man there on the same errand, a Corporal Cutmore of the 1st Battalion.

Rumours of a move on the 2nd and we were busy packing gear. Set off about midnight on a short march to Tingues where we entrained at 4.00am on 3 October. Arrived at Poperinghe about 5.00pm and marched about six weary kilometres to Brown Camp behind Ypres. There was every evidence to show that a big battle was raging in front. On the train we had passed four trainloads of wounded and round the camp the roads were crowded with traffic of every description, from staff cars full of brass hats to heavy lorries full of shells for the guns in front. Our new home was a canvas camp in a sea of mud. Mud that even the mud of Ancre had little in common with. Life there is going to be absolutely terrible and I was praying for my call to come. There was nothing to see where we were, no landscape, nothing but mud, tents and filthy figures crawling about in khaki.

Each tent was surrounded by a three-foot wall of double sandbags and we soon felt thankful for the protection they afforded us. As soon as night set in the Bosch came over in his bombing planes and stayed with us all night. Bombs were dropping with a crash all around us, nasty things that burst on concussion and spread a hail of shrapnel along the ground or rather a foot above it. The battalion had several casualties during the night, one bomb making a direct hit on a tent in C Company and wiping out of existence the twelve men in it. All their remains were buried in one sandbag.

It poured with rain all night and the wind was blowing a gale and we had to keep dashing out with the mallet to knock in the tent pegs. In conversation with some troops the next day who had been round those parts for several weeks, they told us that every night was the same. As soon as darkness came the Bosch planes came and stayed until nearly dawn. Luckily our stay was very short, as our brigade had been picked for the next attack and we had to go back for special training.

On 6 October, 189 Brigade relieved us and motor lorries took us back to Herzele, about thirty kilometres away. We were shoved in the usual class of billets, cowsheds, barns and pigsties, but, nevertheless, a very acceptable change from the tents of Brown Camp. The division was now attached to XVIII Corps commanded by General Maxse, a corps, and a general, famous for hard deeds.

Training started in earnest on the 8th and we had to forget all our previous knowledge and assimilate new methods for attack. I’m afraid my interest in things was very lukewarm. The weather was simply vile, rain practically every day and the state of the ground even so far behind the line as this was simply terrible. We had a special training ground, everything set out as near as possible to the ground over which we should attack. Every German pillbox and machine-gun post was marked, every semblance of a trench or breastwork, every ruin, was there, marked either by a flag or a mound of sandbags. The attack was to come off somewhere about 26 October and was to be made by our brigade, 188, somewhere on Passchendaele, to the right of Poelcapelle.

Captain Ligertwood was red hot about the company coming out with every distinction. He presented each platoon with a beautiful silk flag made for us by his wife; he would carry one for the company. These we should take with us to the battle. He was as fit as exercise could make him and had won all the prizes at the racing meetings on his own nag. He’d made the horse get him there and he intended the company getting him there too. He talked to me one day as we were marching back from a pretty strenuous day and told me he was attaching another sergeant to my platoon who would go over with them. If I received no orders for England before the fight he would see that I hadn’t to go up. The new sergeant was a real acquisition to our Sergeants’ Mess and proved himself a proper scrounger. He went out one night and came back an hour later with the body of a fowl. He had plundered some poor Belgian’s fowl-house. ‘It’s a young cockerel.’ It wasn’t, it was a young cockerel’s great grandmother I would say, and the thing was wasted. We couldn’t get our teeth in it. However, that was only once; on other occasions we fared better and he proved himself a real handy lad in a fowl pen.

Chapter Thirty-Four

18 October 1917 – Blighty and a Commission

Orders along from Brigade Headquarters on the morning of 18 October, special orders for me to proceed to England. Did I dance for joy? Did I throw my steel helmet through the billet window? I did not. Neither did I kiss the sergeant major when he brought me word. I took the news as I took everything else, as some sergeants I know take the whole rum issue. I felt a keen regret at having to leave the battalion, at leaving the friends I had made, lads who had fought with me time after time. I had to leave them now to fight on, while I lived cushily in England for months perhaps.

I had to leave at 6.00pm and walk about fourteen kilometres to the railway station at Arneke. After a whip round the boys and a few hearty handshakes, I set off on my lonely tramp, a cold cheerless night in the station of Arneke, then a painful journey to Boulogne. From 8.00am to 6.00pm. What a journey. I dropped across Cutmore from 1 RM and we chummed together.

Taken to a leave camp at Boulogne, a huge schoolroom where hundreds of men going home on leave were waiting the night for the leave boat in the morning. It was a cold night and our bed was the bare floor with no blankets, just a case of getting down as we were.

Lights had been out about an hour when the anti-aircraft guns boomed out all over the town. The Zeppelins were over and very soon two or three huge explosions testified to the fact that he was getting rid of his load of bombs. There is no question about it: I was terrified and was shaking the whole time like a leaf. To get so near to home and safety and then there’s still the chance of going sky high. About two hours that spasm lasted, and after that I managed about an hour’s sleep. Wasn’t I glad when morning came and with it orders for the boat?

A very uneventful passage across the Channel and a quick run to London. Report at Parliament Street in the morning for instruction. That night I slept at Buckingham Palace Hotel, shorn of all its former gilt and glory. After hours of waiting at the office in Parliament Street I got my papers and warrants for fourteen days’ leave. It was too late to leave London that night so caught the train on 22 October 1917 and arrived home in time for dinner.

So we draw the curtain on another act of the thrilling drama.

Chapter Thirty-Five

Odds and Ends

Before I carry on with my own new troubles and trials I will give an account from the Official History of the RND concerning the doings of my company in the attack at Pas

schendaele shortly after I left them.

One of the finest exploits of this second stage of the attack was the crossing of the Paddebeek (a flooded stream) by Captain Ligertwood’s A Company 2nd Marines. The platoons of this company had gone into action under their own flags, solemnly blessed by the Battalion Chaplain, Father Davey, and taken into action with honour and reverence. These flags were carried through the battle. Captain Ligertwood, three times wounded, led his Company to within sight of their goal, when he fell mortally wounded to rise only once to direct his men to their final objective. This Company, staying on its objective throughout the entire day, were powerless to lift a finger to assist the main battle.

The loss to the RND in three days’ fighting amounted to thirty-two officers and 954 men killed or missing and eighty-three officers and 2,057 men wounded. The division remained in the sector until 6 December, when they received orders to entrain for the Cambrai front and Third Army.

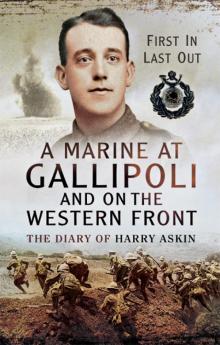

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front