- Home

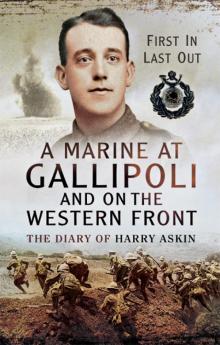

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 20

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 20

Corporal Tolly wandered along after a time with the cheerful news that Billy had been buried by a shell and had gone down with shellshock. Nobody was eager for conversation and the doings for the dawn were never mentioned.

Everybody was eager to get as much sleep as possible before going over. I’m hanged if I could sleep a wink, the smoke and fumes from the shaft bottom almost choking me. My thoughts were on those at home. I knew they would be worrying as I hadn’t been able to write for some time and if our scrap was big enough for a mention in the papers they would imagine things straight away. My thoughts weren’t very lively and as I sat there I was shivering through and through, seated in two or three inches of sloppy mud with a cold, wet wind blowing. The smelly warmth from the fire and from the bodies of the men was just enough to keep my bones from breaking through my skin. My God! And they call this war. We had as much chance of getting out as a celluloid cat has out of Hell.

Things were very quiet except for an occasional rifle shot or a pineapple from Jerry. Every few minutes the reflection from a star-shell would light up the trench, showing everything in its state of filth and rottenness. It was a relief to me when Captain Edwards came along. ‘Get your sections and platoons out on top’ was his order. It was just 5.00am on the 13th when we scrambled out on top of the trench. A thick white fog had settled over everything, blotting out even near objects. The few lights that were being sent up by some tired fed-up German reflected dully through the mist. There wasn’t a sound to be heard as we followed miserably behind Captain Edwards. The men were too fed-up to grouse and that’s saying a lot. We had another trench to cross and about twenty yards in front of that came to our tape where we were spaced out five paces apart with strict instructions to keep at that: there was to be no bunching when we moved forward. My particular spot was a hole made by a 5.9 and I lay down in it and dropped into a half daze, shivering with the damp and cold as though I had ague. Perhaps the feeling of expectancy had something to do with it, although I felt no fear, and I’d little or no doubt as to the ultimate issue as far as I was concerned.

At 5.40am, when the mist was thicker than ever and lay like a wet blanket over the earth, everybody woke up. The earth underneath us shook, just as though a huge mine had been exploded underneath us; the violence of it shook us to our feet. Simultaneously, a deluge of shells poured down in front of us. An idea of the end of the world couldn’t be more awful or swift. It came upon us in a flash, one stupendous soul-splitting crash, then the thousands of shells and we knew that the time had come to walk on.

To the front, showing up through the fog, was a vision of Hell, all fire and brimstone, and our way lay in the very midst of it. We groped our way blindly forward, at the start alone, but by and by through loss of direction and the desire for companionship, in bunches of threes and fours, falling into shell holes, over wire and over the dead bodies of the men of the earlier waves.

Something dropped with a dull thud just by me, exploded but left me untouched. I muttered ‘that’s a b--- pineapple’. About six yards away on my right I could see Tolly stumbling forward. All at once there was a tremendous flash at his feet and he disappeared. I was conscious of fellows going down all round me. We got over our front line and scrambled through our wire in front, on which scores of our men were hanging in all attitudes, and made across no man’s land. The barrage had now lifted and was playing some 250 yards ahead on the German support trench. It had been obvious all through that a German had stuck to his machine gun. As soon as the barrage lifted others joined him and bullets were zipping amongst us with effect.

It was suicide to go on, so, as we came up to the Bosch wire, we took cover in the shell holes until 1 RM should finish their work. We could see the flashes of fire as the bullets struck the wire in front of us. There was one chap already in the hole when I dropped in it, a Lewis-gun ammunition carrier of 1 RM and he was loaded up with about a dozen drums of ammunition. I asked him if he was wounded and he mumbled something and pointed to his ribs. ‘Why don’t you chuck those ruddy things off?’ I said. No, he was alright and he’d stick to his ammunition. I’d an idea he was foxing, but had no more time to bother with him.

Sergeant Osgood fell forward into the shell hole, his face ghastly and the lower part of him covered with blood. ‘Do what you can for me, Harry,’ he gasped. He had got a bullet through his wrist and his hand was hanging on by just a bit of skin and flesh. The main artery was severed and blood was pouring out of him. I hardly knew what to do, but took off my lanyard and tied it tightly round the upper part of his arm, then I put his round, making a slip knot, and pulling it tight. It appeared to stop the flow of blood and I then put a bandage loosely round his wrist. Poor chap, he cried out with the pain and the broken bones rubbed against one another. I settled him as comfortably as possible and turned my attention to matters just around me. I asked the 1 RM chap if I could wrap him up but he said no, he was alright. ‘What the devil are you doing here then?’ I asked. He only mumbled something about being hit, so I left him alone.

I’d no sooner turned away from him when something hit me a terrific blow on the back of my head, knocking me silly for about five minutes. There was no wound though, just a huge bump and I had to shift my steel helmet several degrees to the front to get it to fit. The helmet had a nasty sharp dent in it, so I gave it a few silent thanks for saving my life and looked about me. There was Willett in the next hole with Holt, both of my section. ‘Come on, Corporal,’ Willet yelled, ‘let’s get on!’ ‘Get down you big-headed idiot,’ I yelled back. I could see it was sheer murder to move yet. Being hot-headed on Gallipoli, and getting wounded twice under practically the same circumstances, had taught me a lesson in caution. I realised too that two or three live men would be worth a whole company of dead ones in this scrap.

I saw Sergeant Jock Berry of No.2 Platoon dash forward (full of rum he was), get in the wire and fall dead. Then someone dashed past me from the rear, reached the same spot and got shot down. The bullet must have gone through his chest and out through his haversack, firing one of his red flares. I knew the chap most have at least two Mills bombs there too, and that it wouldn’t be long before they were off. I dashed forward, opened his haversack and threw out the bombs and flare, then turned the chap over. He was past aid though. I got back to Osgood and told him I would try and get the men forward. ‘Good luck, Harry,’ he said, ‘I’ll be alright now.’ We could see the Red Cross men making their way up from the rear. ‘Are you ready, A Company?’ I yelled, and Willet bawled out ‘Come on the Royals!’ and we got on, through the thick belt of wire, over the first German trench and stopped for a breath in his second trench. The first and only live man I saw there was Captain Bissett. He was facing our way and, judging by the expression on his face, he must have thought we were Germans. ‘Where are we, Corporal, and which is our front?’ he asked me when he had gathered himself together. ‘We’re in the second German trench,’ I said, and pointed to our front, which was thick with fog and the smoke of battle. In fact, the fog was thicker and it was impossible to see more than a few yards. I looked round amongst the men and felt thankful for the presence of some of them.

About twenty-five of my company had followed me, amongst whom was Willett, bigheaded and pigheaded, but game, Holt, steady and slow, young Nicholson and Bob Hackett from Wigan, not one of the bravest but willing to face the unknown terror of a German dugout for souvenirs. ‘Let’s clear the dugouts first,’ I said. Thereupon Bob Hackett slung a gas bomb down one of the shafts nearby, following it up with a Mills. About six yards away to the left was the other shaft and in about two minutes we heard a ‘Kamerad’, then a Jerry appeared, followed immediately by a dozen others, all of them half-blinded and choking with the fumes from the gas bomb. Then Hackett made his way cautiously down the first step, a bomb in one hand and his rifle in the other. All the way down the steps we could hear his voice, ‘Come up, you square-headed b******s.’ In about five minutes time he reappeared, with, however, no more G

ermans, but in the possession of an Iron Cross that he had found on one of the tables below. I sent the German prisoners back with Nicholson with orders to come back as soon as he had turned them over.

I went to Captain Bissett who was still sitting on the back of the trench, just then having a drop of something out of a flask. ‘Hadn’t we better be getting on, Sir?’ I asked. I reminded him that our first objective was beyond the Sunken Road, but he said we had better wait there a bit and see what turned up. Then he said that, as he didn’t feel very well, he would sit on the dugout steps for a bit. And that was the swine who drilled us in thick mud for an hour with fixed bayonets at the slope. I shouldn’t be a bit surprised if he had been granted the MC or the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his bit.

I started scouting round then with Willett. First I went left trying to get in touch with some of our lot. The first chap we saw was the 1 RM who was supposed to be wounded. There he was stuck up to the armpits in mud. ‘Get me out of this,’ he moaned. He did look a miserable object. I called two of the other men up and we tried to get him out but couldn’t budge him an inch. ‘I’m sorry mate, but you look like being there for the winter,’ I said. However, I gave him an entrenching tool and told him to dig himself out.

Then I went farther left alone. I had got about twenty-five yards on and had just rounded a traverse when I came face to face with a German standing at the top of a dugout shaft. He had his rifle and bayonet in his hands and I don’t know who was the more surprised. He opened his mouth to shout but too late because just then I pulled my trigger and he went backwards down the steps, and I knew he was dead. I gave a shout for Willett, but he was already on his way. The shot had attracted him, so we proceeded to clear the dugout. Down went a couple of Mills bombs and out came nine Germans headed by an officer. He looked a fierce devil and when he saw only two of us there I thought he was going to turn awkward. However, a threat with my bayonet against his stomach and he was all for peace. Two of our chaps now came up. Hackett was one and I told him to take them on to where the other chaps were. He told me some more of our troops had now turned up.

I went farther left but this time I told Willett to stick to me. The first thing we found was a German Minenwerfer emplacement with two ugly squat guns in it, one already loaded with a 10-inch bomb. Several extra bombs were stacked up in one corner. We left there and twenty yards on came to another huge dugout, which went down forty or fifty steps and down each shaft ran a smoke chute and a ventilation shaft. Scores of German rifles and bayonets were stacked down the shafts and rows of equipment were hung neatly from pegs. We threw a smoke bomb down one shaft and waited at the top of the other but no Germans made their appearance, so we made our way back.

We had seen only dead men belonging to our lot, all from 1 RM who must have got cut up in our barrage. There were scores of them lying about and at the top of the shaft, where I shot the German, one of our men was lying all over the place. His trunk was acting as a doormat for the dugout, one leg and an arm were on the fire-step and the other two limbs were on top of the parapet. God knows where his head was. There wasn’t one wounded man about. All dead.

The fog had lifted a little by now and I could see the German third trench about 200 yards ahead, but who was in it I couldn’t say. Between the two trenches was a stretch of shell-swept mud. I enquired for Captain Bissett when I got back to the first dugout, but was told that the worthy gentleman had gone away suffering from gas. Lieutenant Commander Fairfax had now joined us with remnants of his Howe Battalion and with him was the adjutant, Captain Ellis. I made known to him what I had done and how far I had been and he sent one of his petty officers along with six men and a Lewis gun to act as left-flank post. He said I had better attach myself and my men to his battalion for a time at least. I asked if he knew who was on our right and he said, as far as he knew, only the Germans. They were holding out in a strongpoint, but he would like me to work my way as far to the right as possible and he would then place a strong post there. I set off with Willett and half a dozen more of my chaps. About thirty yards along the trench I could get a good view of the trenches on the right, as the fog had thinned out considerably.

About a hundred yards away, and running as if for dear life, was one of our troops. Two German stick bombs were thrown at him, but even then I thought he would manage to get away. Fate was against him, though, in the shape of a piece of barbed wire over which he fell and the two bombs burst practically on top of him. Bullets zipping into the trench just by me induced me to get down, and we pushed farther along, working our way cautiously round traverse and fire-bay, I with rifle and bayonet ready for immediate action, Willett pressing close behind with a bag of bombs slung over his shoulder, one ready in his hand with the pin out. We got about seventy-five yards on and nothing happened except that Willett and I found ourselves quite alone. The other chaps hadn’t acquired that roaming spirit. We went on for about another thirty yards and came to where a CT led back to the third German trench, and the trench we were in was filled in for about ten yards.

We decided to go back then and report. When we got back I found Jock Saunders (one of our sergeants) had turned up. A cool, steady stick although it was his first time fighting. I reported to the commander and he sent Jock along with six men to form a post at the top of the CT. They took a Lewis gun with them, and Jock was awarded the Military Medal for his little bit.

A lot more of our people had come forward now, amongst them the Stokes trench mortar squad. I went straight to the commander and asked if he could get one or two Stokes guns playing on the redoubt while some of us went forward. He said I could go and ask the Stokes gunner if the guns were alright. I found the sergeant in charge, but he dashed my hopes. Not one gun was fit to fire and no ammunition had got up.

Jerry started slinging ‘Pineapples’ over very soon after and our men were soon getting killed and wounded. Their snipers were busy, too, and were continually getting home on some of our men who were unlucky enough to keep their heads up too long in the same spot.

That redoubt and the third German trench had a fascination for me. Twice I pushed my way past Jock Saunders, over the filled-in trench, where I had to dash for my life and pushed ahead for about fifty yards but came back when I felt how useless it was and how much alone I was. If only the commander had sent a strong bombing party along that trench with me we could have cleared the redoubt. Three times I went down the CT and the last time got to where the trench lost itself in a maze of mud- and water-filled shell holes in which were bodies of Germans, our men and some Scotties, belonging to 51st (Highland) Division who went over on our left, and had evidently lost their direction. One poor devil was stuck straight up in the mud of a shell hole, upside down with only his legs showing from the knees. Fifty yards on my right I could see the German redoubt spitting death and destruction out of numerous loop holes.

On reaching the top of the CT for the last time I saw Captain Gowney of the Ansons nosing round with his field-glasses handy. ‘Hello Corporal Askin,’ he lisped, ‘You still here?’ ‘Yes Sir, but not very still,’ I answered. ‘Get your rifle and find a spot for shooting.’ Then I sniped at the redoubt while he spotted. It was surprising how much movement I could see in the German trench and how many heads were bobbing about. ‘Good! Good!’ Gowney kept exclaiming, ‘I’m sure you got him that time.’

Commander Fairfax sent for Gowney after a time and I got down and went for a chat with Sergeant Saunders. Another chap got up in my place and when I came back ten minutes time he was still there but with a bullet through his brain. Fairfax sent for me then. He said he would have a walk as far right and left as I had been and would pick out suitable places for posts, for the night. Just as we were leaving the first dugout, where he had made his headquarters, we saw two engineers walking over the top, reeling out a telephone wire. One was a Royal Marine captain and the other a sergeant. We yelled to them to get down, but just then the captain got a bullet through his thigh and, instead of droppi

ng straightaway, he stood looking round him with a look of pained surprise on his face. Then we yelled again and he dropped in the shell hole. Meanwhile the sergeant made a dash for our trench, reached the edge and got a bullet through the pit of his stomach. He pitched headlong into the trench just where I was standing. He was dead, killed instantly, and the look of horror and fear on his face was awful to see. He stuck there all that day, pushed into a sitting position in the mud, his mouth wide open, as though he had opened it to yell and had died before he could close it again. His face had turned a horrible green and his eyes remained open and glaring. I’d never seen such a horrible expression on a dead face before.

The commander and I resumed our walk after that episode but he was soon tired, too tired to drag himself to the left where walking was a terrible fatigue. It was simply madness to put one foot down and give it time to settle. It needed the utmost strength to pull it out again and by then the other foot was stuck. One had to sort of run on it and not in it. It was more like the miracle of walking on the water. One had to have faith, otherwise you floundered in a sea of stinking mud.

I was feeling pretty well done up by about 2.00pm. Not a bite or drink since the previous morning and not a wink of sleep. When the commander had finished with me I went along to the dugout where the chap in bits was. It was well lighted with candles and partly furnished. There were two chambers, one evidently for the men and the other for the officers. Each was fitted with wire-netting bunks, stoves and tables. In the officers’ place I found a camera and a whole selection of photographic materials, negatives by the thousand and several printed on postcards, a selection of which I took away with me. I drank a bottle of Bosch mineral water, ate a few of his biscuits and a tin of bully and turned into one of the bunks. Half an hour later came the call ‘Corporal Askin.’ I reckoned to be deaf but it got so damned insistent that I had to roll out. ‘Commander Fairfax wants you at his headquarters,’ somebody told me. I wandered on and he told me to get all the marines together and ‘stand by’ for the redoubt. An artillery liaison officer was there and he was trying to get in touch with the guns. They were to bombard for ten minutes, then we should go over and rush the place. I had a rare job hunting up my marines. Willett had gone back with a piece of Pineapple in his leg. Hackett had gone back with some Germans and I could only find Holt and about half a dozen more. God knows where the others were. I noticed that no one was trying to rouse out the Howes. All the devils were asleep, even the men who were supposed to be on watch. I only wished I could find a place where I could ‘die’ nicely for two or three hours.

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front