- Home

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 13

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 13

We passed through the ship and boarded HMS Grasshopper, a destroyer. There were hundreds packed on her and the only room we could find was right outboard on the starboard side. I could make out Captain Gowney, Cutcher, Mr Mitchell, Chapman and a few more of the leading lights stowed away fairly comfortably between the funnels.

Charlie Hamilton and Billy Hurrell were with me and we decided to drop our gear and sit on it. It was almost an impossible task to do, but we managed it and, just as we got down, the ship shoved off and we left Gallipoli with its thousands of dead to the Turk. As we got about 400 yards from the shore a terrific explosion occurred on V beach. The demolition party had done their work. With that, and the enormous blaze that followed, all the warships standing by opened up. They all had something definite to shell: dumps and camps, trenches and dugouts, both ours and the Turks. We heard as we got on the destroyer that the Turks were already on Y beach and one of our ships had shelled them. Fires broke out all over the place and very soon the whole place was light as day, casting a ruddy glow over the rough surging sea.

We soon realised what life on a destroyer must be. Every few minutes a huge sea would sweep the boat from end to end, making us hang on to anything like grim death. Only a yard separated me from the side of the ship and there was nothing more solid between the sea and me than a steel rope that ran round the ship. We found it impossible to sit down and as soon as we stood up our gear was washed away. I managed to keep hold of my rifle. It acted as a support. We kept wondering where they were taking us and when we should get there. They took us nowhere in particular but up and down the coast of Gallipoli.

The fires on shore were visible the whole time, but nobody was in the least interested. We were all soaked, of course, and starved through and through. About 4.30am cocoa made its appearance on deck, but it was kept strictly to the regions of the funnels. I don’t think I ever remember such a cold, long and miserable hour as the one before the dawn on the 9th. Just as dawn broke we steamed into the harbour at Imbros where the water was calm and still. The place was crowded with ships and our floating palace took us alongside HMS Mars, an old battleship. We were transferred to her and lushed up immediately with hot tea and biscuits.

I found my gear right astern of the destroyer but Charlie had lost everything and so had several more of the chaps. A nine-month collection of souvenirs had gone to Davy Jones. Charlie knew his way about a ship so we followed him and he took us down below where it was hot and we dried in about half an hour. It was impossible for me to sleep. I felt after a time that if I didn’t get out of it into the fresh air I should have about as much nature left in me as a tin of bully.

Everywhere I went on that ship I saw fellows lying about absolutely dead to everything about them. All sorts of regiments were represented onboard and it was a proper scrap to get a wash and nearly a riot when the canteen opened. All they had when they did open were tins of rabbit and biscuits. We ate two tins and a score or so of biscuits between the three of us and then turned in on an iron hatch cover in the NOs’ quarters astern.

We left Imbros at 5.30pm in company of a monitor and arrived once again in Mudros, at dawn next morning.

Chapter Nine

10 January 1916 – Mudros

Landed at 1.00pm and marched to a canvas camp that had been erected for us. Base parties, returned sick and wounded, reinforcements, scroungers and swingers of the lead were awaiting us in large numbers. The number of NCOs that had sprung up from apparently nowhere was surprising. We had Sergeant Owen back again, but looked like losing old Douglas who had swelled to about three times his usual size through dropsy or some such thing.

Tuesday was supposed to be a ‘stand-off’ but, as we happened to be duty platoon of the duty company, it didn’t affect us much. It was graft from Reveille to Lights Out, lumping rations, mails and putting up more tents and marquees. Some ‘stand-off’.

We had a rough week. Three nights we were almost washed and blown out of our camp. It could rain out there. We were lumping mail from the beach for two days. I don’t think there has ever been such a collection before of mail. The mail for the whole division had been dumped there since a week before Christmas. Nearly everybody had a parcel, some two or three, but everything that could go bad was rotten. Scores of bags of parcels had been in the sea and the whole of it had been left lying about in the open.

The 15th was a bitterly cold day with a cutting wind. Kelly Clayton was up before Gowney again for something. A dirty shirt I think it was. Poor old Kelly caught it hot again. I had to take him down to the beach, have him stripped and scrubbed in the sea. It nearly froze me stiff, even with my greatcoat on, but Kelly had to go in. Neither of my two men would touch him; he was too filthy for words and covered with sores where he had scratched himself.

A big party went on leave to England about two days after, Gowney being amongst them. Men who had spent longest on the peninsula were given preference and we poor devils who had been wounded through not shirking our bit were left on the rotten island. Our noble Sergeant Major Chapman went. So did Milne and several more whose attempts at duty got so far as drinking the rum of we poor fools who yelled and shouted and charged. However, we had a fairly decent time on the island drawing a fair amount of money, which went like water in the villages, and having plenty of concerts and football. We stayed under canvas about ten days then moved into hutments about half a mile from the village of Portiano.

Word came round on the 26th that leave to Malta was to be granted, but very few of the eligible men would volunteer. It was perhaps in lieu of English leave. I was confirmed as corporal on the 27th and on the following day had my notice drawn to orders again, where I saw that I had reverted to private again, owing, it said, to over-establishment. That in plain language meant that so many NCOs who had been holding square numbers had come back now that the fighting was over that we poor devils who had fought for our promotion had to stand down.

Captain Williams, our new OC, was very nice about it. He sent for me and another chap who had gone down and told us he was sorry, but it was the custom and he didn’t think we should be very long before we picked up our stripes again. As soon as fighting was mentioned again those same fellows would fade away like snow in a fire, he said. In the same day’s orders we were both appointed paid lance corporals, so that it wasn’t too bad. It appears that that is another custom. We couldn’t revert to lance corporal but must be made private first, then appointed to the lance rank.

Roll on my duration!

The RND took over the whole control of Mudros on l February, all the army having cleared off.

Chapter Ten

12 February 1916 – Malta

Volunteered along with Charlie, Billy and Bob Bayliss to go to Malta on leave. About a hundred went from the division and we all embarked on the Aragon, a RMSP [Royal Mail Steam Packet] boat at 3.30pm on the 13th. All through the Gallipoli stunt she had been anchored in Mudros Bay and was used as a staff ship. Her bottom must have been thick with barnacles. Several civilian spies were on board, brought in from Salonika and more were brought on next day. We left Mudros the same day about 4.00pm and, after three awful rough days, entered the Grand Harbour at Malta on the 17th about noon. We landed about 4.30pm and marched to Spinola where a huge camp had been erected for the reception of the hundreds of casualties expected from the evacuation. They had decided not to give us a few of the comforts that we had missed by not getting wounded.

Lieutenant Colonel ‘Joe’ Mullins was in charge of the camp and, as soon as we got there, he delivered a few kind words to us all. One thing he told us was that if any of us abused the privileges that were granted us we should all be confined to camp for a week. The first night in town and seven men were adrift. A nice start and old Joe fumed. We were sent out downtown in groups of three to hunt these men up and it took us all day to find them. I found one chap down the ‘rag’ in a little drinking house absolutely ‘blotto’. He had been there all night and the old girl in charge of t

he show said he wouldn’t leave. We got him back to camp, and when the sergeant major saw him he told us to take him away and keep him quiet. He hadn’t been reported adrift.

I went down Valletta after with my three chums and had a good spruce up. For one thing we had our lance corporals’ chevrons stitched on our tunics, our buttons cleaned and boots cleaned, the first time I’d felt smart in khaki. Charlie wasn’t a lance corporal so had his two GC1 badges sewn on.

I found Malta a lovely little place, but one that anyone would quickly get fed up with. There seems to be an overabundance of priests and goats here, and an all-pervading smell of garlic. The people are a pretty greasy lot on the whole, nearly all speaking English and all intent on robbing the English. The whole place seems overrun with sailors and mariners, both English and French, but they have apparently nothing better to do than spend their time in the drinking and eating houses in the various ‘rags’. I’ll pass over a description of a ‘rag’ and be content to let it gradually fade from my memory, if it ever will.

The first draft back to the battalion went on the 23rd and the next on 1 March, Billy and Bob amongst them. Colonel Mullins went back too and Colonel Noble took over the camp. The carnival started on 4 March and carried on for three days; three days and nights of drunken foolery. All the people got up in fancy dress and masks and ran mad generally. Charlie and I had a terrific time while it lasted. Most of our time apart from the carnival was passed in rowing ourselves round the little bays that indent the coast.

The weather the whole three weeks was perfect and I felt in a better state of health than ever before. Charlie and I were warned off for draft on 7 March and embarked on the Wahine, a swift, small boat, used for carrying mails between Malta and Mudros. Before the war she’d been a passenger carrier between the north and south Islands of New Zealand. She simply swarmed with cockroaches and there was no provision whatever for troops. Food was just scrambled and the only thing that was served out at all decently was the rum. We left Malta at 7.00am on the 9th in a rough, heavy sea. That boat did roll, and nearly every time her gunwales touched the water.

A sharp lookout was kept the whole way for submarines, but none were spotted. I think we went too fast for them, keeping up a speed the whole way of 18 to 20 knots.

We entered Mudros again at dawn on 11 March, just twelve months after I first entered there. Landed and marched to the RND Detail camp, Colonel Mullins in charge, and who should be adjutant but Captain Gowney! And the first time I saw him, he was on a horse learning to ride. He was an absolute scream and the best turn I’ve seen on a horse.

Chapter Eleven

14 March 1916 – Macedonia

All 1 Brigade was at Stavros, near Salonika, doing outposts and on the 14th all the Malta party embarked on the Snaefell, an armed patrol boat and set off to join our battalions. It was a glorious voyage, and I don’t think anybody who had a trip on this Isle of Man boat before the war saw such strange and beautiful scenery as we saw. We headed first of all for the headland at the mouth of the Gulf of Salonika. This was a huge mountain rising sheer out of the water and visible for miles. The top was hidden in cloud and what we could see of it from a distance appeared quite barren. As we approached it, though, we could see a tiny village nestling at the foot of the cliffs and several small fishing boats lying close inshore. High up in the cliffs were stuck quaint-looking houses, but how on earth people got up and down from them and how they were built was a mystery.

After leaving that, we steamed for a short way up the Gulf of Salonika, then back, in and out of two more large inlets, passing on the way some of the most gorgeous scenery. Great snowcapped mountains, some close to the shore, others far inland, and in two places we could see rivers of ice gradually working their way down to the sea.

On one mountain and about halfway up was a great castle. Just below it was a shadowy wisp of cloud and again above it was more cloud. The effect of it was to take one back to the fairy-tale days and fancies of giants and their castles in the clouds.

It was a perfect day and a perfect sea. Just enough swell on to make one feel lazy and content to lie on deck dreaming and fancying. We finished up about six o’clock near the village of Stavros in Greek Macedonia and only a few miles from the Bulgarian frontier. It was dusk when we landed at a temporary store pier on which a crowd of Greek labourers was working.

A guide from Brigade HQ met us at the ship and conducted us about two miles over a wet swampy plain to HQ where guides from our respective battalions met us. We were at the end of the plain and right ahead of us were mountains up which, our guide informed us, we were to climb. All this after a month of absolute idleness. We had on our full marching order, two blankets, three days’ rations and the usual rifle and 220 rounds of the best. What a journey!

It was pitch dark when we left BHQ and our path was a goat track, now fairly well worn with the passage of troops and mules. Still, it was a difficult passage with our load and the darkness. From around us in the shrub came strange noises and cries and our guide informed us that the country was overrun with jackals. Nobody knew exactly what a jackal was like; we knew it was a wild animal and, judging by its cries, extra wild. Our guide, a most cheerful chap, regaled us with blood-chilling stories of attacks on the troops by these things and how they crept into bivouacs at night and stole all the food. He wasn’t carrying a pack, etc.; we were and consequently hadn’t breath to spare to tell him our views. Jackals weren’t the only things that overran this place. We could hear thousands of frogs croaking from the marshes and pools around us.

We arrived at Battalion HQ about 11.30 but even then we hadn’t done. After waiting an hour there for another guide, from the company this time, we trudged on again. Of course A Company was ‘right of the line’ and camped a mile from Battalion HQ. We reached them at last, 1,090 feet above sea level and the sea only about three miles away. All the chaps were living in bivouacs and, after Charlie and I had wandered about for another half hour, we found Billy and Bob Bayliss and turned in with them. We were in the clouds most of next day but when they did clear managed to get a good view of the surrounding country. We were on top of one of the highest points about here and could get a magnificent view. Behind us lay the sea, a deep blue, except where it broke on the beaches where it was like rolls of snow.

To our front and flanks were high chains of mountains with plains, valleys and a few villages dotted about. The hills around us were covered in a dense scrub of lovely greens. About 3,000 yards away to our right front was the village of Vrusta, and a few miles beyond and along the coast was a great snowcapped mountain, marking the border of Greece and Bulgaria. This mountain was the legendary home of one of the Greek gods. Looking due west and about six miles away was Lake Beshik, and beyond that and seemingly only separated by a narrow strip of land was Lake Langaza. Beyond the lakes – forty miles away – was the town of Salonika. Visible to the left of Salonika was the great Mount Rouzag.

A rough line of trenches had been dug around the forward slope of our hill about fifty feet below the summit and our job was to complete them and clear a space in front of about 150 yards for wiring and field of fire. It was no light task, but one that everybody enjoyed. It was impossible not to enjoy life in such air and surroundings. The scrub was so dense on the hillside that it was almost impossible to get through it, other than by the paths or along the streams. All the cut-down trees and shrubs were dragged to a clearing and burnt. We had some enormous fires.

At first it was almost impossible to sleep at night, for the croaking of the frogs and howling of those wild dogs. I woke up with a start the second night and clutched my stick. One of those jackals was just outside my bivvie but, by the time I was outside, it had faded away into the night. Just below us in the valley ran a small stream which created little ponds in which thousands of frogs lived and thrived. And the row they made was almost unbelievable. Two or three of us made excursions along that stream and slew thousands of the tiny things.

Disc

ipline was pretty slack in the company. Our new OC, Captain Edwards, was far too slack for the crowd of roughs and ‘birds’ that had got into the company. In fact, there wasn’t much stiffness in any of the company officers, Mitchell, Saunders and our own special platoon officer, Surman, who had about as much ambition and backbone as a snake. Sergeant Jeffries was acting CSM and Sergeant Owen was CQMS

The rations were brought up from brigade every day by mules, but were far from satisfying. Our appetites were simply enormous and we couldn’t get enough bully and biscuits even to make up. We saw some lovely sunsets from our hilltop. The sun set exactly behind the lakes and the effect on the water was grand.

Billy, Bob and I took it in turns for orderly corporal. Our work on that day consisted of reporting dinner to the sub of the day and accompanying him on his round of the trenches at night. A guard was mounted in the trenches at night with two sentry posts. Mr Saunders was best to get on with but, of course, I always clicked with Mitchell. I’m certain that chap was mad. I used to go down for him about 10.00pm, but usually he’d be playing cards with the other three. If he was winning he’d knock off and go the rounds then, but if he was losing he’d keep on playing and tell me to give him a shake about 1.30 or 2.00am. Poor thing! He used to tremble the whole way and would jump and start at the slightest sound or rustle from the bushes. ‘What’s that?’ he whispered once, ‘have you got your rifle, Corporal?’ I hadn’t. I always carried a stick. He told me in future I must always carry my rifle. His revolver was always out, shaking about in a most alarming manner. He arranged to go over the top one night and drop silently into the trench by the right snipers’ pit. His idea was to try and catch the sentries napping. I let the corporal of the guard know and told him to wait for us behind a certain traverse, then challenge. He did challenge and poor Mitchell was speechless. He couldn’t answer the challenge and the corporal repeated it. ‘Who are you?’ he snapped, “Answer quick or I’ll put a bullet through you.’ Mitchell was still speechless so I had to answer for him. Even that didn’t cure him and he tried a few more stunts after that. Surman was just as bad, but got in a worse state of funk than Mitchell.

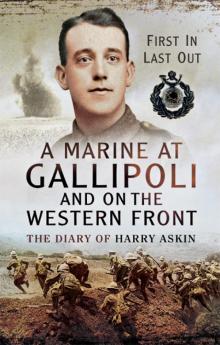

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front