- Home

- Harry Askin

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Page 11

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front Read online

Page 11

We had a fine view of Krithia from the redoubt and it appeared quite near. A monitor was lying off in the Gulf of Saros on Wednesday, sending 14-inch shells right into the village. It was possible to see what a mass of ruins the village was. Not a single house remained complete, some being just heaps of charred wood and stone, others just mere skeletons of houses. The lines of windmills were badly battered and I should imagine it most unhealthy for the Turks in occupation of the place. The ground all around the place was a maze of trenches and wire. The Turk evidently intended to stick to that place as long as he could.

Digging again all night and about 11.30pm we had to take cover. The French exploded a big mine and both sides went at it ding-dong for the crater. Shrapnel and bullets flew about and we got quite a lot of both. This lasted about an hour and when it was over we carried on digging.

This redoubt had been built in case we were pushed back at any time. Several had been constructed across the peninsula and manning them would enable the troops from the firing line to retreat in an orderly manner with an opportunity to construct another line of defence. Our redoubt was about twenty yards square and consisted of a broad fire trench on all four sides, thus obtaining an all-round field of fire. It was well wired towards the front and flanks and the only entrance was by the trench leading from the left. This trench was protected by a loophole in the redoubt which commanded a stretch of straight trench for twenty-five yards. The chunk of earth in the middle of the redoubt was cut into three gun positions but were not occupied, except by Cutcher and Sergeant Douglas for sleeping quarters.

Chapter Eight

December 1915 – The Evacuation

We heard on 16 December that our troops had evacuated the Suvla district. That was a nasty smack for us. Heard too that the Turks had given us seven days to clear a big field ambulance from above W beach as they intended bombarding. Very sporting of them. Up in the firing line again by 6.30pm and manning a part of the Horseshoe fifty yards from the Turk. We had orders to keep a strict watch as the Turks had been observed massing for an attack in that sector.

The French were reported to be leaving the peninsula and we were to take over their line and rest camp. Troops appeared to be getting fairly thin in numbers this side of our line. The Turks in our sector got it hot on Saturday. Our 10-inch guns and heavy trench mortars bumped them all morning. I reckoned that would upset his plans for an attack.

Everyone felt pretty well done up. I think it was the worst time we had had for sleep. It was dig or hump rations from going up to getting relieved. Everybody felt thankful when the 2nd Londons came wandering up about 7.00pm. They were only two hours late, but they came. We all collapsed on reaching our camp. The journey down had been awful. Heard that the Scotties were attacking again the following day, bombardment to start at 2.00pm and every gun to fire 300 rounds.

Eggs and bacon for breakfast on Sunday morning. The eggs were supposed to have come off a Turkish prize but they looked like Egyptians. I was lucky and got two good ones. We were to move at 11.00pm to take over the French rest camp. Of course it was 2.00pm when we actually did move, just as all our guns opened up on the Turkish lines and Achi Baba. It was by far the finest bombardment I had witnessed since the landing. Every ship and every gun was going at it ‘hell for leather’ and the whole front of Achi Baba was blotted out by dust and smoke. This was kept up until 4.00pm and we heard afterwards that all our troops and nearly every gun had got safely away from Anzac.

What was going to happen to us?

I expected that, in a few days’ time, we would all be swept or blown into the sea.

The Scots advanced and managed to take two trenches, H.11a and H.12a, but failed to get their real objective. The opposition was too strong. One would have imagined that after such a terrific bombardment there would be no living thing left to oppose an advance. There was so much of the ground to hit though, and a trench really takes up so little of the space, and the individual man is a mere speck and an invisible one.

To be in a bombardment though, one’s feelings are entirely different to that of observation. It is as though you and your bit of trench are standing out absolutely alone like some huge landmark and that all the enemy’s guns are concentrated on you and your particular trench.

We found our new dugouts fine. The French were certainly more thorough in their efforts at comfort than we were. Each dugout could accommodate a platoon and was fitted with splinter-proof roofs and shell-proof backs. Weren’t they busy!

Lice, big fat white ones, continually dropped on us from the roof and walls, and if there’s one kind of louse that I particularly detest more than another, it’s a white one. This camp was occupied before us by French colonial troops and I didn’t think they were very clean at the best of times. All the French troops except some artillery were leaving the peninsula in a few days’ time.

On Tuesday we had a heavy rainstorm which carried on all night and swamped the whole camp. Poor old Cutcher was washed out of his little place and, later on, the whole thing collapsed, burying all his gear. He seemed absolutely out of place and quite unable to adapt himself to his surroundings. The troops up on the line were having a lively time by the sound of things. The Turk was sending over some great black shells, and, for down in the rest camps he had a special thing, something specially invented to put the wind up hardened troops. I suppose the Turk knew that, after a time, troops lose all fear of shrapnel, providing of course that we had cover handy, so he or the Bosch had thought out something new. This new one was like two shells in one. First, they burst in the air like an ordinary shell, then again on contact with the ground or whatever it hit. Real devilish things. One went right into one of C Company’s dugouts, nearly wiping out No. 11 Platoon. Griggs had a fright on Wednesday morning. He was taking an empty dixie back to the galley when one of these things went off, part of it hitting the dixie and knocking it yards away. He came dashing back to the dugout, shaking like a leaf and nothing would induce him to go out again that day. I had the wind up for about two days but on the Thursday morning Billy Hurrell and I were outside, throwing some more earth on our roof, when two of these things burst a matter of feet away. We could feel the concussion as they burst and could hear the bits of casing as they whizzed by, but we were both safe. I lost all fear of them from then, and felt confident as I had done all the time that I should pull through alright.

On digging fatigues on Thursday morning with the engineers who are drilling and blasting rock. The Turk was sending over heavy black stuff all day, some of it unpleasantly close to us.

Promoted to full corporal on Christmas Eve, a nice present for Christmas, especially the pay part. I immediately proceeded to put myself another stripe on either shoulder strap by the aid of indelible pencil. That was where we wore our stripes. Early on in the campaign, all NCOs ripped off their stripes and became, in all outward appearance, as ordinary soldiers. By doing so they stood so many chances less of being picked off by a sniper. Later on, and when the fear of the sniper had diminished somewhat, they wished for their stripes back, but they were unobtainable in that heathen land; hence the indelible.

The Turks bombarded our trenches heavily all morning and then made a very weak-hearted attempt at an infantry attack, but our guns were waiting and immediately squashed it.

I believe Johnny was guessing all he could as to what our game was; if we were going to hit him in a new place, or clear off as we had done at Suvla and Anzac. The 29th Division came round here again from Suvla and the troops appeared to be getting thick again. We had three Taubes over all day Christmas Eve and after tea they dropped three fairly big bombs in Fleming Gully, just on our right. There were several casualties, one of our transport men being blown to bits with his three mules.

No fatigues on Christmas day. Peace and goodwill towards men. I don’t think.

We had plenty of sport and games and I came off with a prize of 5/- (25p). My luck must have been in. We had a change for dinner. It should have been fr

esh meat but we had bully stew with dried veg and a sweet, half a pound of deadly Christmas pudding out of a tin. We were on half rations, the reason being the new adventure at Salonika. All our supply ships were being diverted to Greece instead of Turkey. We heard the cheerful news, too, that the ship that was bringing our Christmas mail and parcels had been turned back to Egypt or Mudros. A fresh batch of reinforcements were on her too, but were not allowed to land. A Taube came over and three of our planes tried to catch it but with no success. It was a sight worth watching though.

I clicked for a nice little job. Clayton was up before Captain Gowney for having a dirty rifle and when Gowney set eyes on Kelly he straightaway went off. ‘Send for Corporal Askin,’ he yelled. I went, ‘Get two men and take Private Clayton to the nearest well and have him scrubbed.’ Poor old Kelly howled but he got the scrubbing. I wouldn’t touch him though. His legs were awful, one mass of septic sores where he had scratched himself. I made him report sick as soon as we got back and he got another good drubbing from Jimmy Ross.

Parade 9.15am on the 26th for the line. Captain Gowney had had a party up to the firing line to see which and what was the best method of getting up. Practically the whole way up the CT was knee deep in mud and water. He told us we could either take off our boots and stockings and roll our trousers above our knees, or put sandbags over them. The majority favoured sandbags, but I think the others were better off. It was a terrible journey and Gowney led off like a racehorse. The rear of the company didn’t get up till the following morning. We had a pretty rough time leaving camp. The Turk must have spotted us as we were lined up for inspection for he shelled us heavily with those double-event HE things.

There were several casualties in the battalion and we were all fairly glad to get up the line. We were to do two days in support, first in the old Trotman Road sector. Our platoon was on the extreme right of the battalion sector, in an old Turkish trench. We had a most cheerful night for a kick off, a severe thunderstorm with a heavy downpour of rain. The rain carried on till the Monday noon and the state of the trench was something to remember forever. The mud almost dragged our boots off our feet.

I thought that I had lost all fear of shells. Those two days completely changed my views and put a fresh fear of death and mutilation into me, and in everybody else. From noon when the rain ceased to 3.00pm we were subjected to the worst bombardment that I had ever been in. Shrapnel Saturday – 1 May – was nothing compared with this three hours. It wasn’t the quantity of the shells that mattered so much; it was the quality and weight.

Great big howitzer shells that came down on us at an angle of about 60 degrees and which made a noise similar to an express train dashing at full speed through a station. Every other noise was swallowed up in that great terrifying roar. Whizz-bangs kept bursting on the parapet but we never heard them and then, when these big ones burst, it was more like an earthquake and an eruption at the same time. The earth would tremble and shake and where the shell had burst a great column of earth and smoke would shoot up a hundred feet into the air. Long after they had burst, huge lumps of earth and iron casing kept whizzing down to earth at a terrific speed. There were one or two shelters in our trench capable of holding about twenty men. No. 2 Platoon had crowded into one – a mad thing to do – and one of these shells went right through the top and burst in the ground underneath, blowing the whole thing high in the air. There was a huge crater where it had been, and sheets of iron, beams of wood and boxes of ammunition were blown for scores of yards. Most of the fellows were buried, and when got out had to be taken away suffering from shellshock as well as wounds. Two men were blown to little bits. No matter who you looked at they all had fear on their faces. Some chaps who before this were apparently nerveless were now shaking with fear and everybody had a tendency to bunch together and keep moving up and down a trench. I was terrified but tried hard not to show it and if there was one thing I hated in a bombardment it was a crowd. As I heard a shell coming I got down in the bottom of the trench and turned my face towards the roar. I saw about four of those shells just before they pitched into the ground. Once after I’d seen one pitch in I saw a mass of wreckage, lumps of wood, sandbags, sheets of iron, men and parts of men go up in the air. It was in the Anson lines on our right and we heard after that fifteen men had been blown to bits in one shelter. The concussion was enough to kill anybody. Rations went begging that first day. Charlie Hamilton came along the trench with a plate full of dinner. He was asking for Cutcher, but I told him we hadn’t seen him since the shelling started and it wasn’t much use walking that dinner round. Even if we found Cutcher, he wouldn’t want his dinner. No doubt he would be at Company HQ where the shells weren’t going. Billy and I had his dinner and it was good; Charlie can cook!

Everybody started cursing the fleet and our heavy artillery for not opening. Not a shell went over from our side until 2.30. Two of our aeroplanes went over there and spotted for the heavies. The last big shell came over about 3.00pm and we began to sort things out a bit and got back a few of our good spirits.

The second fire-bay from me on the left was filled in, and some of the chaps were busy digging it into shape again. No one was underneath, luckily, but a bit farther on, where No. 2 Platoon had caught it, the trench was in a frightful state. Sheets of corrugated iron and huge logs of wood were torn to shreds and the whole place smelt of burnt chemicals and smouldering rag. Bits of uniform and equipment and broken rifles were all over the place. On what was left of the fire-step stood an old and semi-deformed man called David. He had been on watch the whole strafe and refused to be relieved. He had been blown off the step twice with the concussion and knocked off once with a huge lump of earth, but still he stuck it. Word was passed along at 3.30 to reinforce the front line as the Turk showed signs of an attack. We weren’t wanted, however, and C Company, who were in the line, didn’t thank us for going up. They could manage all the blurry Turks who came their way. No doubt, but they hadn’t had a shell. In fact, our company was the only one in the battalion to catch those big ones. Got back to our own trench after about an hour and carried on clearing up.

Our company had had about twenty to twenty-five casualties during the afternoon. Later on we found out the apparent reason for the shelling. About twenty yards behind our trench was another very narrow, deep trench and cut off from it were covered-in places full of big French land torpedoes, demoiselles they called them. That’s most likely what the Turks over at Chanak or Kilid Bahr were trying to hit. If he did hit a dump, I reckoned everyone within a hundred yards would be killed straight off.

News came along later that one of the Turks’ submarines had been netted by the Fleet at the mouth of the Dardanelles.

We had another dizzy time on Tuesday. It started with a Taube flying low over our lines about 7.00am, very likely spotting for the result of the previous day’s shelling. We opened up on it with our rifles but with no result. He flew about until he was ready to go. There was no interference from our planes or anti-aircraft guns.

Later on, I watched some shells from a French battery bursting behind Krithia and we heard later that they had put out two Turkish siege guns. The uppermost thought in the mind of every man in A Company was ‘will he start again with those accursed shells?’ Start he did and the fun commenced in our bay. We were all sitting on the fire-step eating stew – which was rather better than usual – myself, Billy, Jimmy Rimmer, Baird and Bolan. All at once a whizz-bang burst on the parapet and Bolan sprang up with a wild yell. His canteen went over the back of the trench, stew and all, and he dashed off down the trench yelling ‘stretcher-bearers’. All our dinners were spoilt and the big dixie was full of dirt, and it wasn’t nice dirt. Of course everybody laughed; we had to, as we always did when anything just missed us.

Presently Bolan came back looking rather shamefaced. A piece of hard earth had hit him on the back of the neck, not even making a lump. We hadn’t much chance to laugh at him, because we heard one of those big devils coming. Ever

ybody got down and said a little prayer. ‘Oh God don’t let this thing hit me and I’ll be good for ever,’ or something to that effect. The shell burst about twenty yards in front and Captain Gowney’s runner, Micky, got two fair portions of casing in his ribs.

The shells came pretty thick and fast after that and the company got quite panicky. The men started, first moving to the right, then to the left, getting as far as possible from the place where the last shell burst. ‘Why can’t we reinforce the firing line?’ chaps kept asking. No shells were dropping there. I tried to find Cutcher. I thought if he kept knocking about among his own platoon it would tend to quieten the men a bit. I knew that if many more shells came over, some of the chaps would be bolting. I couldn’t find him though. Perhaps he had gone to find someone else in the firing line.

A corporal and several more men went away from No. 2 Platoon suffering from shellshock. Six more were killed in the company and eighteen wounded. One shell pitched in the back of our parados. Everybody in the bay was down flat thinking that the next second we should all be twenty feet in the air. It was a dud and we all laughed like idiots. We heard that our chaplain, the Reverend Moore, was up at Company Headquarters burying the dead in the open behind the trench.

Everybody was thankful when we saw our aeroplanes come over about 4.00pm. About a dozen went over at once and the Turks’ big guns ‘piped down’. We could hear our aeroplanes shortly after, dropping bombs on the forts across the narrows I suppose.

Some of the chaps found a base belonging to one of the big shells, a great piece of steel, ten inches across, and on the bottom was stamped the British War Department’s stamp and the date of manufacture. They must have been shells that were sent to Bulgaria before she turned against us. How nice to be blown up and shaken up by your own shells.

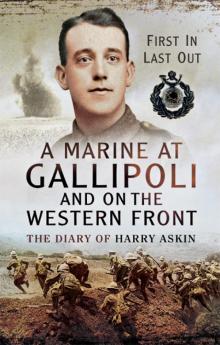

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front

A Marine at Gallipoli on the Western Front